DNS

What is DNS?

The Domain Name System (DNS) is the phonebook of the Internet. Humans access information online through domain names, like nytimes.com or espn.com. Web browsers interact through Internet Protocol (IP) addresses. DNS translates domain names to IP addresses so browsers can load Internet resources.

Each device connected to the Internet has a unique IP address which other machines use to find the device. DNS servers eliminate the need for humans to memorize IP addresses such as 192.168.1.1 (in IPv4), or more complex newer alphanumeric IP addresses such as 2400:cb00:2048:1::c629:d7a2 (in IPv6).

How does DNS work?

The process of DNS resolution involves converting a hostname (such as www.example.com) into a computer-friendly IP address (such as 192.168.1.1). An IP address is given to each device on the Internet, and that address is necessary to find the appropriate Internet device - like a street address is used to find a particular home. When a user wants to load a webpage, a translation must occur between what a user types into their web browser (example.com) and the machine-friendly address necessary to locate the example.com webpage.

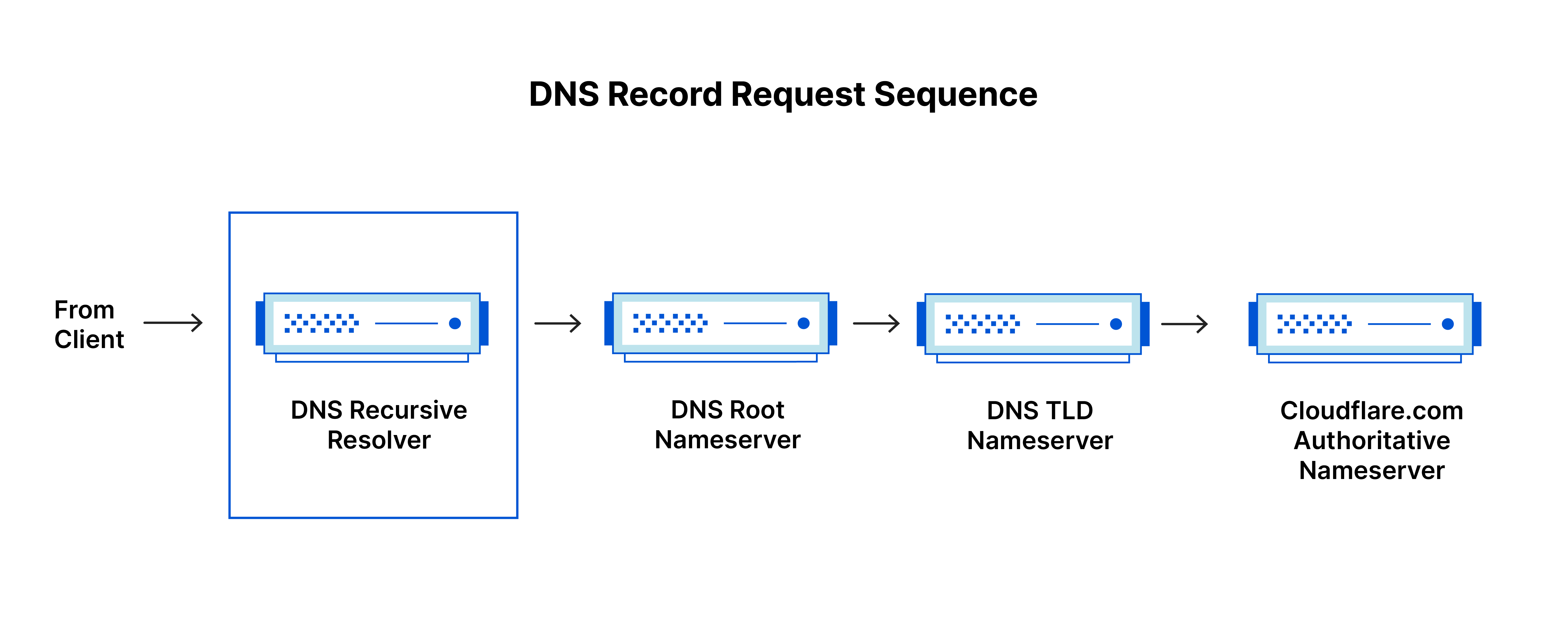

In order to understand the process behind the DNS resolution, it’s important to learn about the different hardware components a DNS query must pass between. For the web browser, the DNS lookup occurs "behind the scenes" and requires no interaction from the user’s computer apart from the initial request.

4 DNS services unvolved in loading a webpage

-

DNS recursor - The recursor can be thought of as a librarian who is asked to go find a particular book somewhere in a library. The DNS recursor is a server designed to receive queries from client machines through applications such as web browsers. Typically the recursor is then responsible for making additional requests in order to satisfy the client’s DNS query.

-

Root nameserver - The root server is the first step in translating (resolving) human readable host names into IP addresses. It can be thought of like an index in a library that points to different racks of books - typically it serves as a reference to other more specific locations.

-

TLD nameserver - The top level domain server (TLD) can be thought of as a specific rack of books in a library. This nameserver is the next step in the search for a specific IP address, and it hosts the last portion of a hostname (In example.com, the TLD server is “com”).

-

Authoritative nameserver - This final nameserver can be thought of as a dictionary on a rack of books, in which a specific name can be translated into its definition. The authoritative nameserver is the last stop in the nameserver query. If the authoritative name server has access to the requested record, it will return the IP address for the requested hostname back to the DNS Recursor (the librarian) that made the initial request.

Difference between an authoritative DNS server and a recursive DNS resolver

Both concepts refer to servers (groups of servers) that are integral to the DNS infrastructure, but each performs a different role and lives in different locations inside the pipeline of a DNS query. One way to think about the difference is the recursive resolver is at the beginning of the DNS query and the authoritative nameserver is at the end.

Recursive DNS resolver

The recursive resolver is the computer that responds to a recursive request from a client and takes the time to track down the DNS record. It does this by making a series of requests until it reaches the authoritative DNS nameserver for the requested record (or times out or returns an error if no record is found). Luckily, recursive DNS resolvers do not always need to make multiple requests in order to track down the records needed to respond to a client; caching is a data persistence process that helps short-circuit the necessary requests by serving the requested resource record earlier in the DNS lookup.

Authoritative DNS server

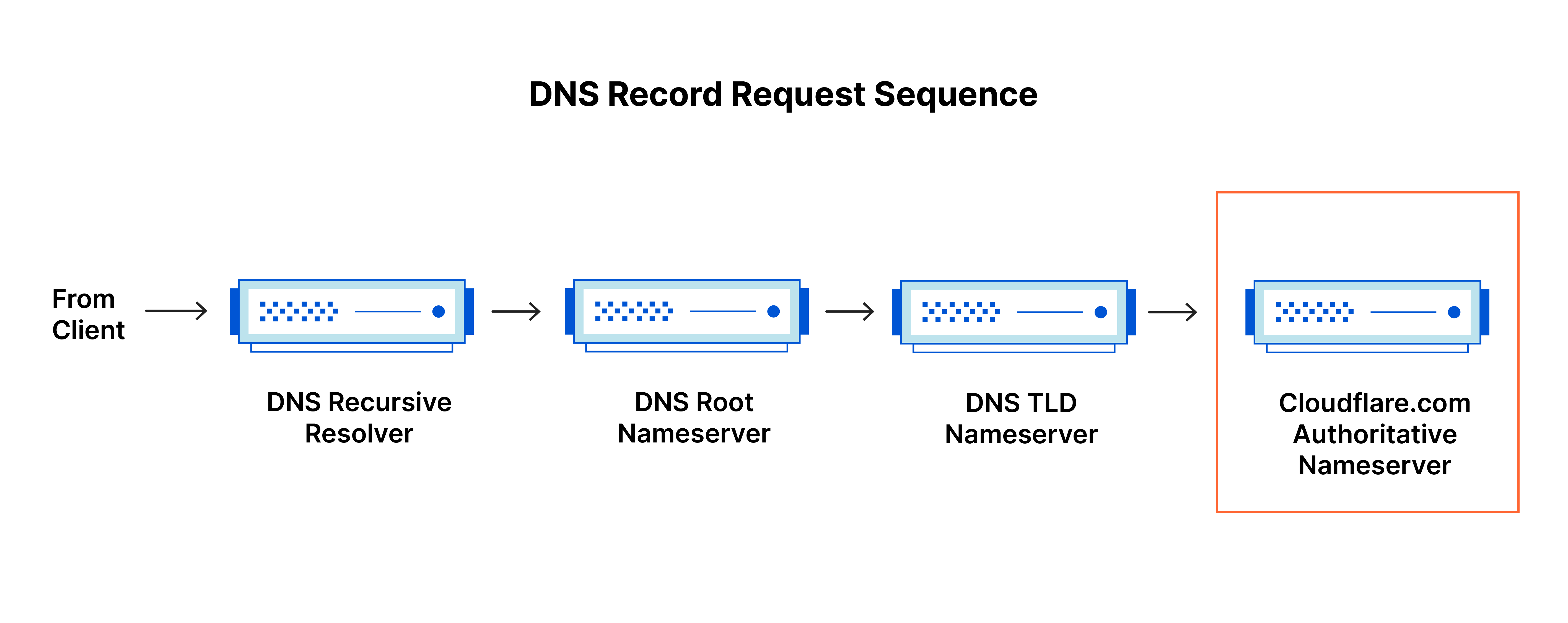

Put simply, an authoritative DNS server is a server that actually holds, and is responsible for, DNS resource records. This is the server at the bottom of the DNS lookup chain that will respond with the queried resource record, ultimately allowing the web browser making the request to reach the IP address needed to access a website or other web resources. An authoritative nameserver can satisfy queries from its own data without needing to query another source, as it is the final source of truth for certain DNS records.

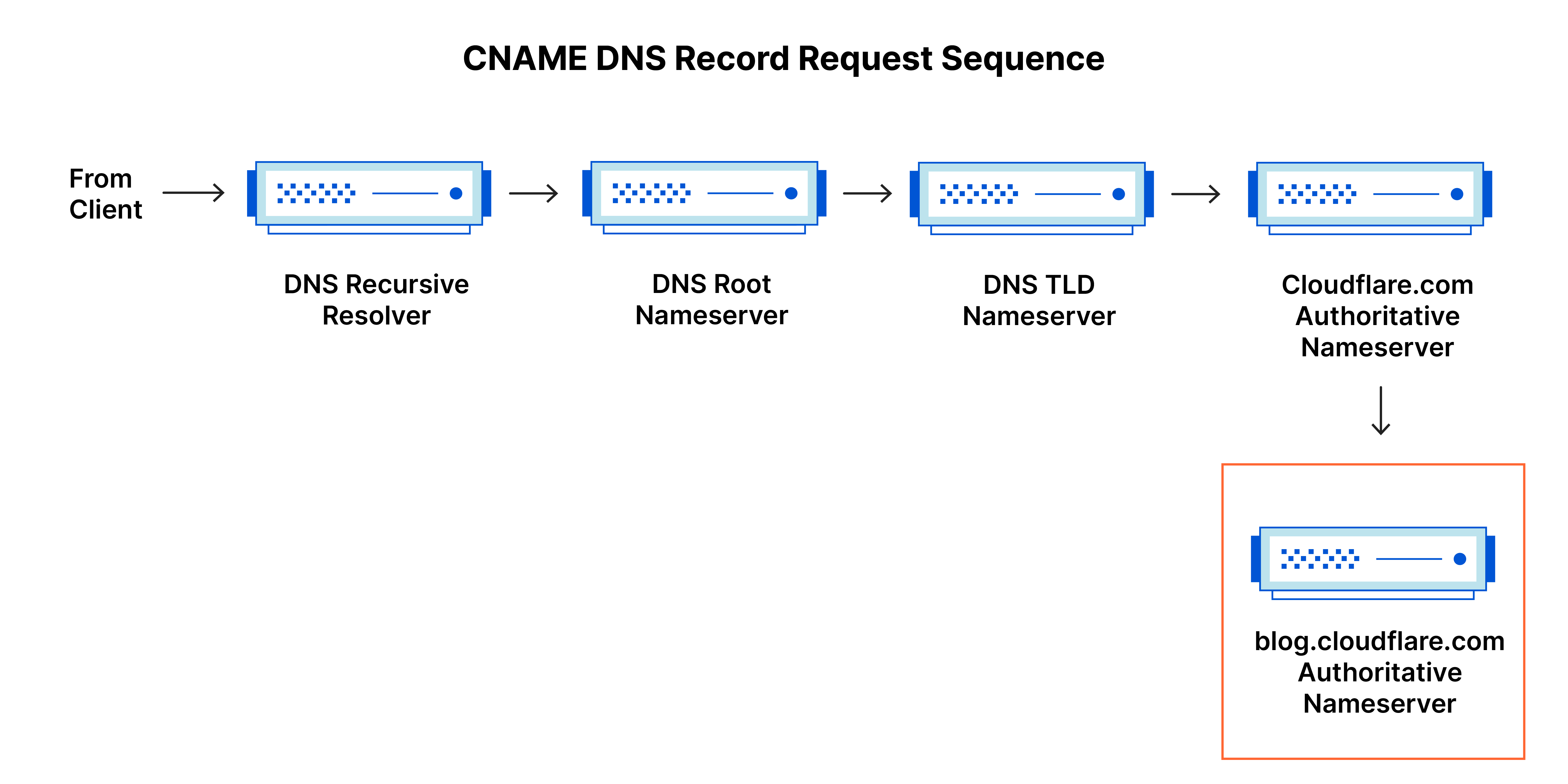

It’s worth mentioning that in instances where the query is for a subdomain such as foo.example.com or blog.cloudflare.com, an additional nameserver will be added to the sequence after the authoritative nameserver, which is responsible for storing the subdomain’s CNAME record.

What happens when a user visits a website

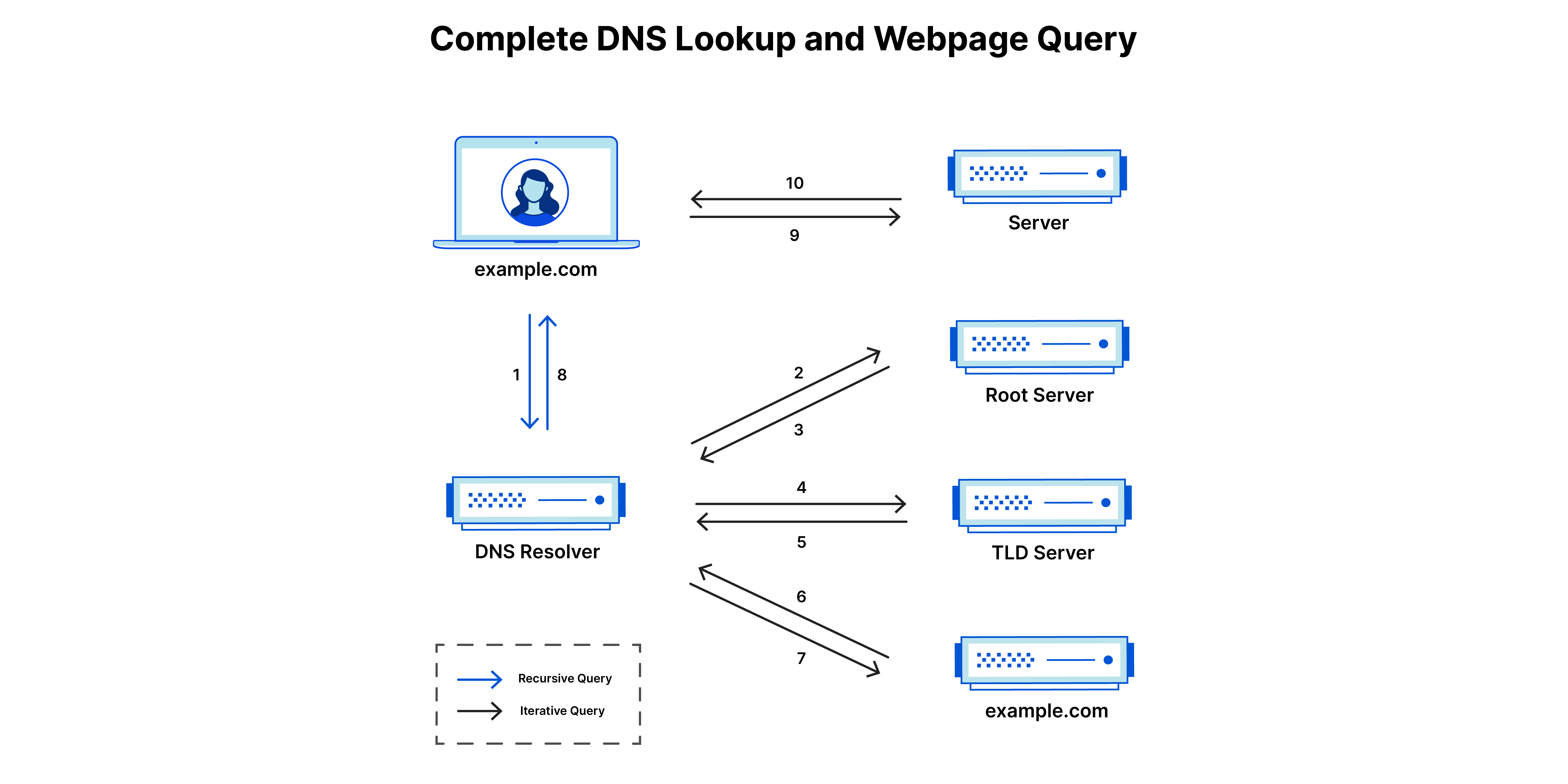

- A user types ‘example.com’ into a web browser and the query travels into the Internet and is received by a DNS recursive resolver.

- The resolver then queries a DNS root nameserver (.).

- The root server then responds to the resolver with the address of a Top Level Domain (TLD) DNS server (such as .com or .net), which stores the information for its domains. When searching for example.com, our request is pointed toward the .com TLD.

- The resolver then makes a request to the .com TLD.

- The TLD server then responds with the IP address of the domain’s nameserver, example.com.

- Lastly, the recursive resolver sends a query to the domain’s nameserver.

- The IP address for example.com is then returned to the resolver from the nameserver.

- The DNS resolver then responds to the web browser with the IP address of the domain requested initially.

Once the 8 steps of the DNS lookup have returned the IP address for example.com, the browser is able to make the request for the web page:

- The browser makes a HTTP request to the IP address.

- The server at that IP returns the webpage to be rendered in the browser.

Types of DNS queries?

In a typical DNS lookup three types of queries occur. By using a combination of these queries, an optimized process for DNS resolution can result in a reduction of distance traveled. In an ideal situation cached record data will be available, allowing a DNS name server to return a non-recursive query.

3 types of DNS queries:

-

Recursive query - In a recursive query, a DNS client requires that a DNS server (typically a DNS recursive resolver) will respond to the client with either the requested resource record or an error message if the resolver can't find the record.

-

Iterative query - in this situation the DNS client will allow a DNS server to return the best answer it can. If the queried DNS server does not have a match for the query name, it will return a referral to a DNS server authoritative for a lower level of the domain namespace. The DNS client will then make a query to the referral address. This process continues with additional DNS servers down the query chain until either an error or timeout occurs.

-

Non-recursive query - typically this will occur when a DNS resolver client queries a DNS server for a record that it has access to either because it's authoritative for the record or the record exists inside of its cache. Typically, a DNS server will cache DNS records to prevent additional bandwidth consumption and load on upstream servers.

Where does DNS caching occur?

The purpose of caching is to temporarily stored data in a location that results in improvements in performance and reliability for data requests. DNS caching involves storing data closer to the requesting client so that the DNS query can be resolved earlier and additional queries further down the DNS lookup chain can be avoided, thereby improving load times and reducing bandwidth/CPU consumption. DNS data can be cached in a variety of locations, each of which will store DNS records for a set amount of time determined by a time-to-live (TTL).

Browser DNS caching

Modern web browsers are designed by default to cache DNS records for a set amount of time. The purpose here is obvious; the closer the DNS caching occurs to the web browser, the fewer processing steps must be taken in order to check the cache and make the correct requests to an IP address. When a request is made for a DNS record, the browser cache is the first location checked for the requested record.

In Chrome, you can see the status of your DNS cache by going to chrome://net-internals/#dns.

Operating system (OS) level DNS caching

The operating system level DNS resolver is the second and last local stop before a DNS query leaves your machine. The process inside your operating system that is designed to handle this query is commonly called a “stub resolver” or DNS client. When a stub resolver gets a request from an application, it first checks its own cache to see if it has the record. If it does not, it then sends a DNS query (with a recursive flag set), outside the local network to a DNS recursive resolver inside the Internet service provider (ISP).

When the recursive resolver inside the ISP receives a DNS query, like all previous steps, it will also check to see if the requested host-to-IP-address translation is already stored inside its local persistence layer.

The recursive resolver also has additional functionality depending on the types of records it has in its cache:

-

If the resolver does not have the A records, but does have the NS records for the authoritative nameservers, it will query those name servers directly, bypassing several steps in the DNS query. This shortcut prevents lookups from the root and .com nameservers (in our search for example.com) and helps the resolution of the DNS query occur more quickly.

-

If the resolver does not have the NS records, it will send a query to the TLD servers (.com in our case), skipping the root server.

-

In the unlikely event that the resolver does not have records pointing to the TLD servers, it will then query the root servers. This event typically occurs after a DNS cache has been purged.

DNS Flood

A DNS flood is a type of distributed denial-of-service attack (DDoS) where an attacker floods a particular domain’s DNS servers in an attempt to disrupt DNS resolution for that domain. If a user is unable to find the phonebook, it cannot lookup the address in order to make the call for a particular resource. By disrupting DNS resolution, a DNS flood attack will compromise a website, API, or web application's ability respond to legitimate traffic. DNS flood attacks can be difficult to distinguish from normal heavy traffic because the large volume of traffic often comes from a multitude of unique locations, querying for real records on the domain, mimicking legitimate traffic.

The function of the Domain Name System is to translate between easy to remember names (e.g. example.com) and hard to remember addresses of website servers (e.g. 192.168.0.1), so successfully attacking DNS infrastructure makes the Internet unusable for most people. DNS flood attacks constitute a relatively new type of DNS-based attack that has proliferated with the rise of high bandwidth Internet of Things (IoT) botnets like Mirai. DNS flood attacks use the high bandwidth connections of IP cameras, DVR boxes and other IoT devices to directly overwhelm the DNS servers of major providers. The volume of requests from IoT devices overwhelms the DNS provider’s services and prevents legitimate users from accessing the provider's DNS servers.

DNS flood attacks differ from DNS amplification attacks. Unlike DNS floods, DNS amplification attacks reflect and amplify traffic off unsecured DNS servers in order to hide the origin of the attack and increase its effectiveness. DNS amplification attacks use devices with smaller bandwidth connections to make numerous requests to unsecured DNS servers. The devices make many small requests for very large DNS records, but when making the requests, the attacker forges the return address to be that of the intended victim. The amplification allows the attacker to take out larger targets with only limited attack resources.

Mitigation of DNS Flood

DNS floods represent a change from traditional amplification-based attack methods. With easily accessible high bandwidth botnets, attackers can now target large organizations. Until compromised IoT devices can be updated or replaced, the only way to withstand these types of attacks is to use a very large and highly distributed DNS system that can monitor, absorb, and block the attack traffic in realtime.

DNS Record Types

A Record

The "A" stands for "address" and this is the most fundamental type of DNS record: it indicates the IP address of a given domain. For example, if you pull the DNS records of cloudflare.com, the A record currently returns an IP address of: 104.17.210.9.

| Name | Record Type | Value | TTL |

|---|---|---|---|

| @ | A | 192.0.2.1 | 14400 |

The "@" symbol in this example indicates that this is a record for the root domain, and the "14400" value is the TTL (time to live), listed in seconds. The default TTL for A records is 14,400 seconds. This means that if an A record gets updated, it takes 240 minutes (14,400 seconds) to take effect.

The vast majority of websites only have one A record, but it is possible to have several. Some higher profile websites will have several different A records as part of a technique called round robin load balancing, which can distribute request traffic to one of several IP addresses, each hosting identical content.

The most common usage of A records is IP address lookups: matching a domain name (like "cloudflare.com") to an IPv4 address. This enables a user's device to connect with and load a website, without the user memorizing and typing in the actual IP address. The user's web browser automatically carries this out by sending a query to a DNS resolver.

DNS A records are also used for operating a Domain Name System-based Blackhole List (DNSBL). DNSBLs can help mail servers identify and block email messages from known spammer domains.

AAA Record

DNS AAAA records match a domain name to an IPv6 address. DNS AAAA records are exactly like DNS A records, except that they store a domain's IPv6 address instead of its IPv4 address.

IPv6 is the latest version of the Internet Protocol (IP). One of the important differences between IPv6 and IPv4 is that IPv6 addresses are longer than IPv4 addresses. The Internet is running out of IPv4 addresses, just as there are only so many possible phone numbers for a given area code. But IPv6 addresses offer exponentially more permutations and thus far more possible IP addresses.

| Name | Record Type | Value | TTL |

|---|---|---|---|

| @ | AAAA | 2001:0db8:85a3:0000:0000:8a2e:0370:7334 | 14400 |

Like A records, AAAA records enable client devices to learn the IP address for a domain name. The client device can then connect with and load the website.

AAAA records are only used when a domain has an IPv6 address in addition to an IPv4 address, and when the client device in question is configured to use IPv6. While all domains have one or more IPv4 addresses and accompanying A records, not all domains have IPv6 addresses, and not all user devices are configured to use IPv6.

However, IPv6 is growing in adoption. This will likely continue to be the case because the number of available IPv4 addresses is rapidly diminishing, often forcing multiple devices to share an IPv4 address.

CNAME record

A "canonical name" (CNAME) record points from an alias domain to a "canonical" domain. A CNAME record is used in lieu of an A record, when a domain or subdomain is an alias of another domain. All CNAME records must point to a domain, never to an IP address. Imagine a scavenger hunt where each clue points to another clue, and the final clue points to the treasure. A domain with a CNAME record is like a clue that can point you to another clue (another domain with a CNAME record) or to the treasure (a domain with an A record).

For example, suppose blog.example.com has a CNAME record with a value of "example.com" (without the "blog"). This means when a DNS server hits the DNS records for blog.example.com, it actually triggers another DNS lookup to example.com, returning example.com’s IP address via its A record. In this case we would say that example.com is the canonical name (or true name) of blog.example.com.

Oftentimes, when sites have subdomains such as blog.example.com or shop.example.com, those subdomains will have CNAME records that point to a root domain (example.com). This way if the IP address of the host changes, only the DNS A record for the root domain needs to be updated and all the CNAME records will follow along with whatever changes are made to the root.

A frequent misconception is that a CNAME record must always resolve to the same website as the domain it points to, but this is not the case. The CNAME record only points the client to the same IP address as the root domain. Once the client hits that IP address, the web server will still handle the URL accordingly. So for instance, blog.example.com might have a CNAME that points to example.com, directing the client to example.com’s IP address. But when the client actually connects to that IP address, the web server will look at the URL, see that it is blog.example.com, and deliver the blog page rather than the home page.

| Name | Record Type | Value | TTL |

|---|---|---|---|

| blog.example.com | CNAME | is an alias of example.com | 32600 |

In this example you can see that blog.example.com points to example.com, and assuming it is based on our example A record we know that it will eventually resolve to the IP address 192.0.2.1.

Can a CNAME record point to another CNAME record? Yes, but pointing a CNAME record to another CNAME record is inefficient because it requires multiple DNS lookups before the domain can be loaded — which slows down the user experience — but it is possible. For example, blog.example.com could have a CNAME record that pointed to www.example.com's CNAME record, which then pointed to example.com's A record.

For blog.example.com:

| Name | Record Type | Value | TTL |

|---|---|---|---|

| blog.example.com | CNAME | is an alias of www.example.com | 32600 |

For www.example.com:

| Name | Record Type | Value | TTL |

|---|---|---|---|

| www.example.com | CNAME | is an alias of example.com | 32600 |

This configuration adds an extra step to the DNS lookup process and should be avoided if possible. Instead, the CNAME records for both blog.example.com and www.example.com should point directly to example.com.

NS record

NS stands for ‘nameserver,’ and the nameserver record indicates which DNS server is authoritative for that domain (i.e. which server contains the actual DNS records). Basically, NS records tell the Internet where to go to find out a domain's IP address. A domain often has multiple NS records which can indicate primary and secondary nameservers for that domain. Without properly configured NS records, users will be unable to load a website or application.

Here is an example of an NS record:

| Name | Record Type | Value | TTL |

|---|---|---|---|

| @ | NS | ns1.exampleserver.com | 216 |

Note that NS records can never point to a canonical name (CNAME) record.

What is a nameserver?

A nameserver is a type of DNS server. It is the server that stores all DNS records for a domain, including A records, MX records, or CNAME records.

Almost all domains rely on multiple nameservers to increase reliability: if one nameserver goes down or is unavailable, DNS queries can go to another one. Typically there is one primary nameserver and several secondary nameservers, which store exact copies of the DNS records in the primary server. Updating the primary nameserver will trigger an update of the secondary nameservers as well.

When multiple nameservers are used (as in most cases), NS records should list more than one server. Learn more about DNS servers.

When should NS records be updated or changed?

Domain administrators should update their NS records when they need to change their domain's nameservers. For instance, some cloud providers provide nameservers and require their customers to point to them.

Admins may also wish to update their NS records if they want a subdomain to use different nameservers. In the example above, the nameserver for example.com is ns1.exampleserver.com. If the example.com admin wanted blog.example.com to resolve via a ns2.exampleserver.com instead, they could set this up by updating the NS record.

When NS records are updated, it may take several hours for the changes to be replicated throughout the DNS.

MX record

A DNS 'mail exchange' (MX) record directs email to a mail server. The MX record indicates how email messages should be routed in accordance with the Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP, the standard protocol for all email). Like CNAME records, an MX record must always point to another domain.

| Name | Record Type | Priority | Value | TTL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| @ | MX | 10 | mailhost1.example.com | 45000 |

| @ | MX | 20 | mailhost2.example.com | 45000 |

The 'priority' numbers before the domains for these MX records indicate preference; the lower 'priority' value is preferred. The server will always try mailhost1 first because 10 is lower than 20. In the result of a message send failure, the server will default to mailhost2.

The email service could also configure this MX record so that both servers have equal priority and receive an equal amount of mail:

| Name | Record Type | Priority | Value | TTL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| @ | MX | 10 | mailhost1.example.com | 45000 |

| @ | MX | 10 | mailhost2.example.com | 45000 |

This configuration enables the email provider to equally balance the load between the two servers.

What is the process of querying an MX record?

Message transfer agent (MTA) software is responsible for querying MX records. When a user sends an email, the MTA sends a DNS query to identify the mail servers for the email recipients. The MTA establishes an SMTP connection with those mail servers, starting with the prioritized domains (in the first example above, mailhost1).

What is a backup MX record?

A backup MX record is just an MX record for a mail server with a higher 'priority' value (which means a lower priority), so that under normal circumstances mail will go to the more prioritized servers. In the first example above, mailhost2 would be the 'backup' server because email traffic will be handled by mailhost1 as long as it is up and running.

Can MX records point to a CNAME?

A CNAME record is used for referencing a domain's alias instead of its actual name. CNAME records typically point to an A record (in IPv4) or AAAA record (in IPv6) for that domain. However, MX records have to point directly to a server's A record or AAAA record. Pointing to a CNAME is forbidden by the RFC documents that define how MX records function.