Redis

What is Redis?

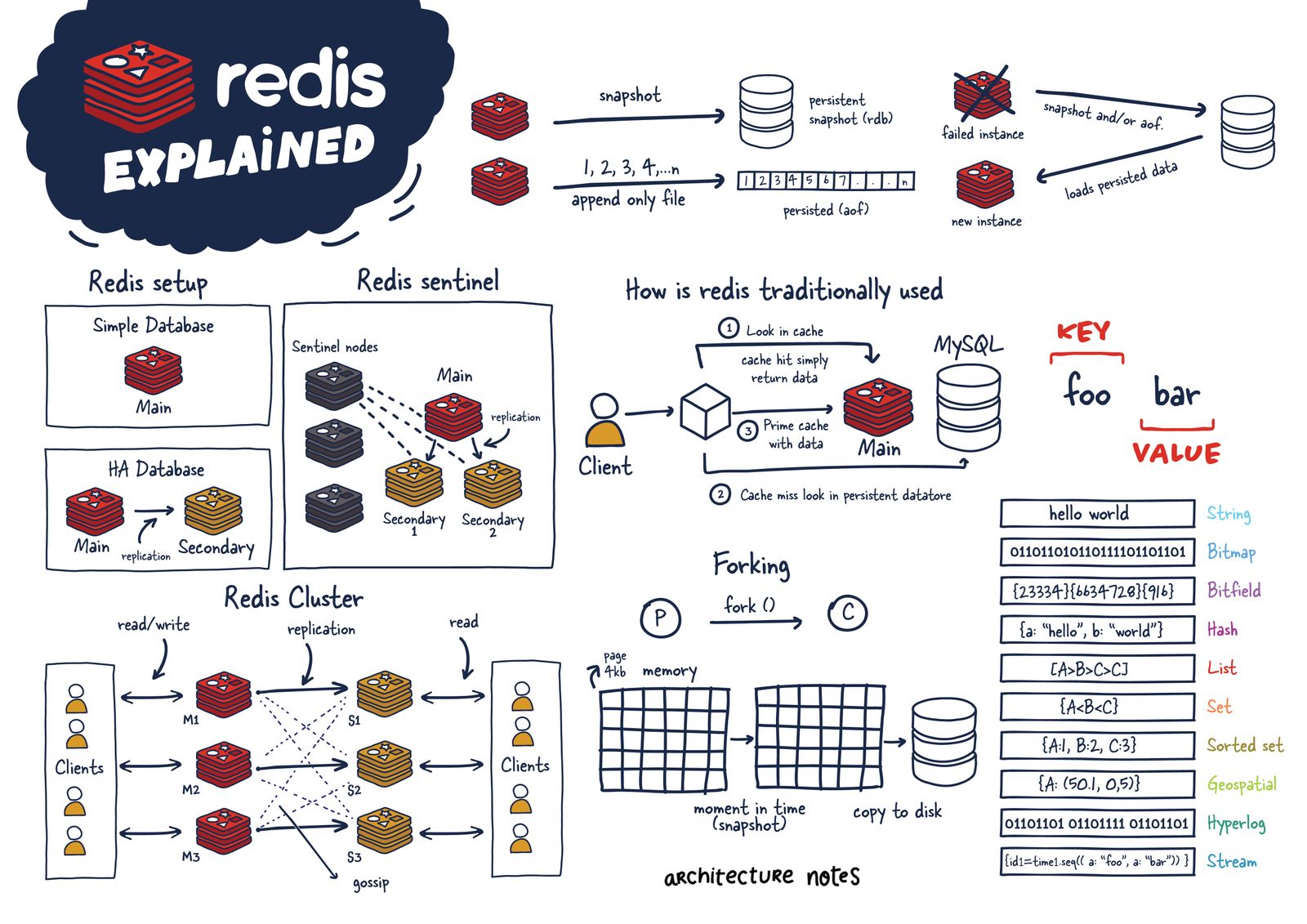

Redis, which stands for Remote Dictionary Server, is a fast, open-source, in-memory key-value data store for use as a database, cache, message broker, and queue.

You can run atomic operations, like appending to a string; incrementing the value in a hash; pushing an element to a list; computing set intersection, union and difference; or getting the member with highest ranking in a sorted set.

In order to achieve performance, Redis works with an in-memory dataset. Depending on your use case, you can persist it either by dumping the dataset to disk every once in a while, or by appending each command to a log. Persistence can be optionally disabled, if you just need a feature-rich, networked, in-memory cache.

Redis is a popular choice for caching, session management, gaming, leaderboards, real-time analytics, geospatial, ride-hailing, chat/messaging, media streaming, and pub/sub apps.

Primarily, Redis is an in-memory database used as a cache in front of another "real" database like MySQL or PostgreSQL to help improve application performance. It leverages the speed of memory and alleviates load off the central application database for:

- Data that changes infrequently and is requested often

- Data that is less mission-critical and is frequently evolving.

- Examples of above data can include session or data caches and leaderboard or roll-up analytics for dashboards.

However, for many use cases, Redis offers enough guarantees that it can be used as a full-fledged primary database. Coupled with Redis plug-ins and its various High Availability (HA) setups, Redis as a database has become incredibly useful for certain scenarios and workloads.

Another important aspect is that Redis blurred the lines between a cache and datastore. Important note to understand here is that reading and manipulating data in memory is much faster than anything possible in traditional datastores using SSDs or HDDs.

Important latency and bandwidth numbers every software engineer to should be aware of.

Important latency and bandwidth numbers every software engineer to should be aware of.

Originally Redis was most commonly compared to Memcached, which lacked any nonvolatile persistence at the time.

| Feature | Memcached | Redis |

|---|---|---|

| Sub-millisecond latency | Yes | Yes |

| Developer ease of use | Yes | Yes |

| Data partitioning | Yes | Yes |

| Support for a broad set of programming languages | Yes | Yes |

| Advanced data structures | - | Yes |

| Multithreaded architecture | Yes | - |

| Snapshots | - | Yes |

| Replication | - | Yes |

| Transactions | - | Yes |

Although now configurable in how it persists data to disk, when it was first introduced, Redis used snapshots where asynchronous copies of the data in memory were persisted to disk for long-term storage. Unfortunately, this mechanism has the downside of potentially losing your data between snapshots.

Redis Architecture

Before we start discussing Redis internals, let's discuss the various Redis deployments and their trade-offs.

We will be focusing mainly on these configurations:

- Single Redis Instance

- Redis HA

- Redis Sentinel

- Redis Cluster

Depending on your use case and scale, you can decide to use one setup or another.

Single Redis Instance

Single Redis instance is the most straightforward deployment of Redis. It allows users to set up and run small instances that can help them grow and speed up their services. However, this deployment isn't without shortcomings. For example, if this instance fails or is unavailable, all client calls to Redis will fail and therefore degrade the system's overall performance and speed.

Given enough memory and server resources, this instance can be powerful. A scenario primarily used for caching could result in a significant performance boost with minimal setup. Given enough system resources, you could deploy this Redis service on the same box the application is running.

Understanding a few Redis concepts on managing data within the system is essential. Commands sent to Redis are first processed in memory. Then, if persistence is set up on these instances, there is a forked process on some interval that facilitates data persistence RDB (very compact point-in-time representation of Redis data) snapshots or AOF (append-only files).

These two flows allow Redis to have long-term storage, support various replication strategies, and enable more complicated topologies. If Redis isn't set up to persist data, data is lost in case of a restart or failover. If the persistence is enabled on a restart, it loads all of the data in the RDB snapshot or AOF back into memory, and then the instance can support new client requests.

With that said, let us look into more distributed Redis setups you might want to use.

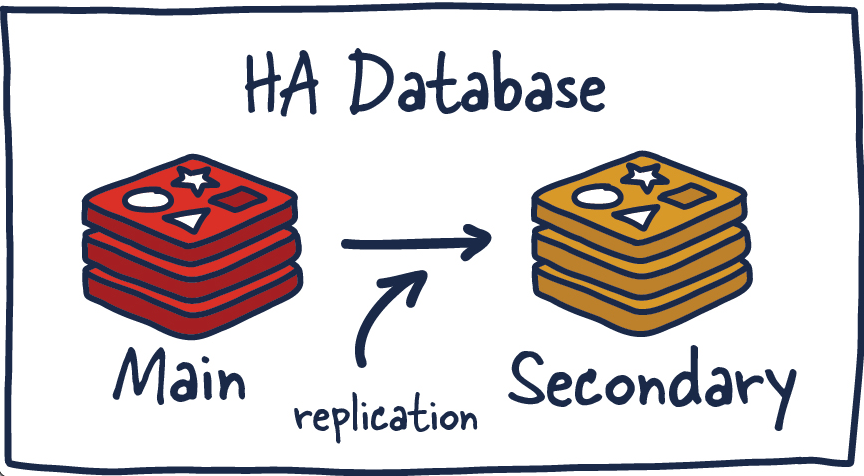

Redis HA

Another popular setup with Redis is the main deployment with a secondary deployment that is kept in sync with replication. As data is written to the main instance it sends copies of those commands, to a replica client output buffer for secondary instances which facilitates replication. The secondary instances can be one or more instances in your deployment. These instances can help scale reads from Redis or provide failover in case the main is lost.

There are several new things to consider in this topology since we have now entered a distributed system that has many fallacies you need to consider. Things that were previously straightforward are now more complex.

Redis Replication

At the base of Redis replication (excluding the high availability features provided as an additional layer by Redis Cluster or Redis Sentinel) there is a leader follower (master-replica) replication that is simple to use and configure. It allows replica Redis instances to be exact copies of master instances. The replica will automatically reconnect to the master every time the link breaks, and will attempt to be an exact copy of it regardless of what happens to the master.

This system works using three main mechanisms:

-

When a master and a replica instances are well-connected, the master keeps the replica updated by sending a stream of commands to the replica to replicate the effects on the dataset happening in the master side due to: client writes, keys expired or evicted, any other action changing the master dataset.

-

When the link between the master and the replica breaks, for network issues or because a timeout is sensed in the master or the replica, the replica reconnects and attempts to proceed with a partial resynchronization: it means that it will try to just obtain the part of the stream of commands it missed during the disconnection.

-

When a partial resynchronization is not possible, the replica will ask for a full resynchronization. This will involve a more complex process in which the master needs to create a snapshot of all its data, send it to the replica, and then continue sending the stream of commands as the dataset changes.

Redis uses by default asynchronous replication, which being low latency and high performance, is the natural replication mode for the vast majority of Redis use cases. However, Redis replicas asynchronously acknowledge the amount of data they received periodically with the master. So the master does not wait every time for a command to be processed by the replicas, however it knows, if needed, what replica already processed what command. This allows having optional synchronous replication.

Replication ID Explained

Every Redis master has a replication ID: it is a large pseudo random string that marks a given story of the dataset. Each master also takes an offset that increments for every byte of replication stream that it is produced to be sent to replicas, to update the state of the replicas with the new changes modifying the dataset. The replication offset is incremented even if no replica is actually connected, so basically every given pair of:

Replication ID, offset

More explicitly, when the Redis replica instance is just a few offsets behind the main instance, it receives the remaining commands from the primary, which is then replayed on its dataset until it is in sync. If the two instances cannot agree on a replication ID or the offset is unknown to the main instance, the replica will then request a full synchronization. This involves a primary instance creating a new RDB snapshot and sending it over to the replica. While this transfer is happening, the main instance is buffering all the intermediate updates between the snapshot cut-off and current offset to send to the secondary once it is in sync with the snapshot. Once complete, replication can continue as normal.

If an instance has the same replication ID and offset, they have precisely the same data. Now you may be wondering why a replication ID is required. When a Redis instance is promoted to primary or restarts from scratch as a primary, it is given a new replication ID. This is used to infer the prior primary instance from which this newly promoted secondary was replicating. This allows for the ability to perform a partial synchronization (with other secondaries) since the new primary instance remembers its old replication ID.

For example, two instances, primary and secondary, have the identical replication ID but offsets that differ by a few hundred commands, meaning that if those were replayed on the instance that is just behind in offset, they would have the same dataset. Now if the replication IDs differ entirely, and when we are unaware of the previous replication ID (no common ancestor) of the newly demoted (and rejoining) secondary. We will need to perform an expensive full sync.

Alternatively if we are aware of previous replication ID we can then reason about how to get the data in sync since we are able to reason about common ancestor they both shared and the offset is again meaningful for a partial sync.

The reason why Redis instances have two replication IDs is because of replicas that are promoted to masters. After a failover, the promoted replica requires to still remember what was its past replication ID, because such replication ID was the one of the former master. In this way, when other replicas will sync with the new master, they will try to perform a partial resynchronization using the old master replication ID. This will work as expected, because when the replica is promoted to master it sets its secondary ID to its main ID, remembering what was the offset when this ID switch happened. Later it will select a new random replication ID, because a new history begins.

When handling the new replicas connecting, the master will match their IDs and offsets both with the current ID and the secondary ID (up to a given offset, for safety). In short this means that after a failover, replicas connecting to the newly promoted master don't have to perform a full sync.

In case you wonder why a replica promoted to master needs to change its replication ID after a failover: it is possible that the old master is still working as a master because of some network partition: retaining the same replication ID would violate the fact that the same ID and same offset of any two random instances mean they have the same data set.

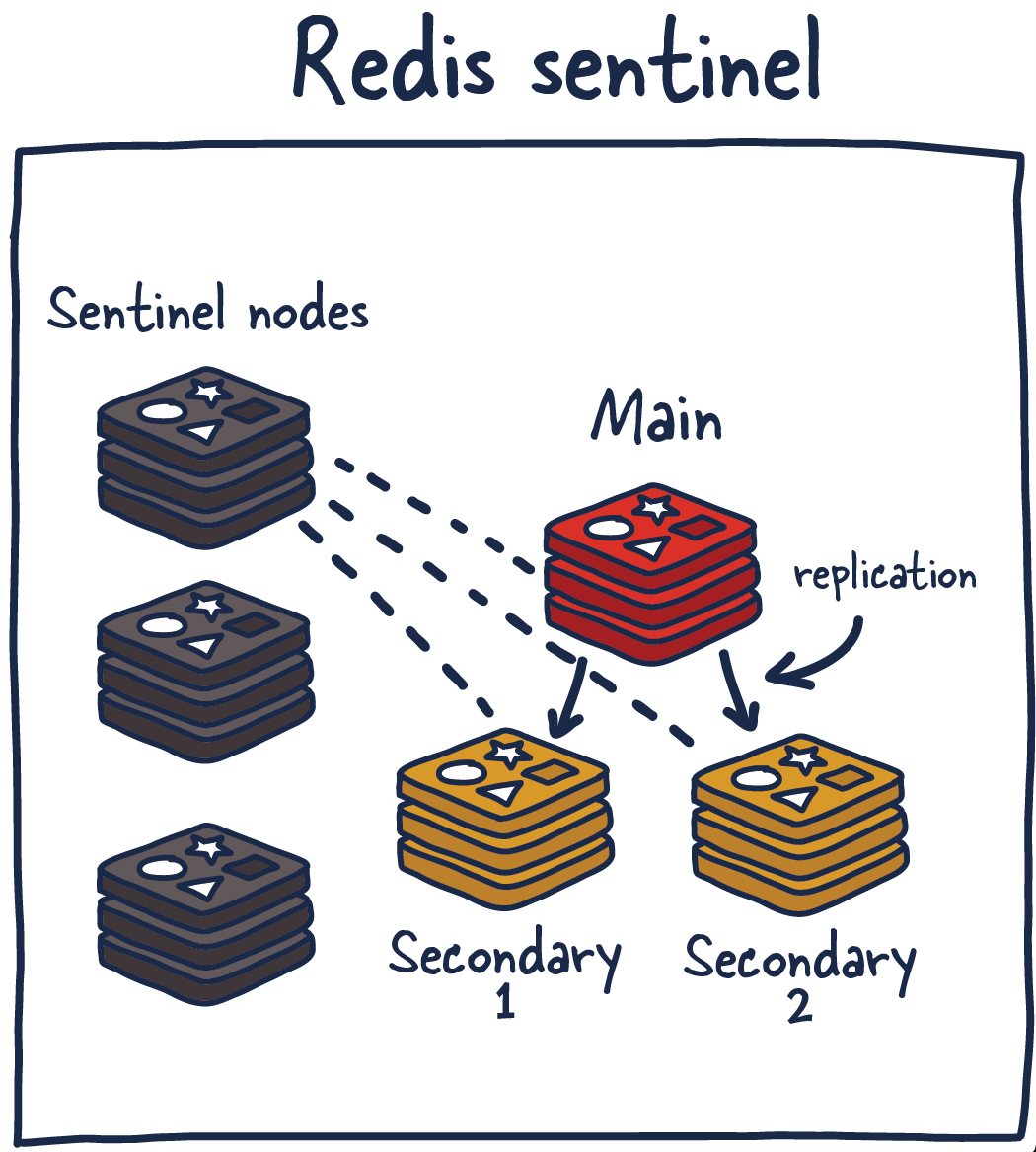

Redis Sentinel

Sentinel is a distributed system. As with all distributed systems, Sentinel comes with several advantages and disadvantages. Sentinel is designed in a way where there is a cluster of sentinel processes working together to coordinate state to provide high availability for Redis. Afterall you wouldn't want the system protecting you from failure to have its own single point of failure.

Sentinel is responsible for a few things. First, it ensures that the current main and secondary instances are functional and responding. This is necessary because sentinel (with other sentinel processes) can alert and act on situations where the main and/or secondary nodes are lost. Second, it serves a role in service discovery much like Zookeeper and Consul in other systems. So when a new client attempts to write something to Redis, Sentinel will tell the client what current main instance is.

So sentinels are constantly monitoring availability and sending out that information to clients so they are able to react to them if they indeed do failover.

Here are its responsibilities:

- Monitoring — ensuring main and secondary instances are working as expected.

- Notification — notify system admins about occurrences in the Redis instances.

- Failover management — Sentinel nodes can start a failover process if the primary instance isn't available and enough (quorum of) nodes agree that is true.

- Configuration management — Sentinel nodes also serve as a point of discovery of the current main Redis instance.

Using Redis Sentinel in this way allows for failure detection. This detection involves multiple sentinel processes agreeing that current main instance is no longer available. This agreement process is called Quorum. This allows for increased robustness and protection against one machine misbehaving and being unable to reach the main Redis node.

This setup isn't without its disadvantages so we are going to run through a few recommendations and best practices when using Redis Sentinel.

You can deploy Redis Sentinel in several ways. Honestly to make any sane recommendation I would need more context than I currently have about your system. As general guidance I would recommend running a sentinel node along aside each of your application servers (if possible) so you also don't need to factor in network reachability differences between sentinel nodes and clients who are actually using Redis.

You can run Sentinel alongside the Redis instances or even on independent nodes, but that complicates things in different ways. I recommend at least running three nodes with a quorum of at least two. Here is a simple chart breaking down numbers of servers in a cluster and associated quorum and tolerated failures that are sustainable.

| Number of Servers | Quorum | Number Of Tolerated Failures |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 2 | 0 |

| 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 4 | 3 | 1 |

| 5 | 3 | 2 |

| 6 | 4 | 2 |

| 7 | 4 | 3 |

| Replication | - | Yes |

| Transactions | - | Yes |

Table of number of servers and quorum with number of tolerated failures.

This will vary from system to system but general idea stands.

Let's take a moment to think through what could go wrong in such a setup. If you run this system long enough, you will run into all of them.

- What if the sentinel nodes fall out of quorum?

- What if there is a network split which puts the old main instance in the minority group? What happens to those writes? (Spoiler: they are lost when the system recovers fully)

- What happens if the network topologies of sentinel nodes and client nodes (application nodes) are misaligned? 😬

There are no durability guarantees, especially since persistence (see below) to disk is asynchronous. There is also the nagging problem of when clients find out about new primaries, how many writes did we lose to an unaware primary? Redis recommends that when new connections are established that they should query for the new primary. Depending on the system configuration, that could mean a significant data loss.

There are a few ways to mitigate the level of losses if you force the main instance to replicate writes to a minimum of one secondary instance. Remember, all Redis replication is asynchronous and has its trade-offs. So it will need to independently track acknowledgement and if they aren't confirmed by at least one secondary, the main instance will stop accepting writes.

Redis Cluster

I am sure many have thought about what happens when you can't store all your data in memory on one machine. Currently, the maximum RAM available in a single server is 24TIB, presently listed online at AWS. Granted, that's a lot, but for some systems, that isn't enough, even for a caching layer.

Redis Cluster allows for the horizontal scaling of Redis.

So let's get some terminology out of the way; once we decide to use Redis Cluster, we have decided to spread the data we are storing across multiple machines, known as sharding. So each Redis instance in the cluster is considered a shard of the data as a whole.

This brings about a new problem. If we push a key to the cluster, how do we know which Redis instance (shard) is holding that data? There are several ways to do this, but Redis Cluster uses algorithmic sharding.

To find the shard for a given key, we hash the key and mod the total result by the number of shards. Then, using a deterministic hash function, meaning that a given key will always map to the same shard, we can reason about where a particular key will be when we read it in the future.

What happens when we later want to add a new shard into the system? This process is called resharding.

Assuming the key foo was mapped to shard zero after introducing a new shard, it may map to shard five. However, moving data around to reflect the new shard mapping would be slow and unrealistic if we need to grow the system quickly. It also has adverse effects on the availability of the Redis Cluster.

Redis Cluster has devised a solution to this problem called Hashslot, to which all data is mapped. There are 16K hashslot. This gives us a reasonable way to spread data across the cluster, and when we add new shards, we simply move hashslots across the systems. By doing this, we just need to move hashlots from shard to shard and simplify the process of adding new primary instances into the cluster.

This is possible without any downtime, and minimal performance hit. Let's talk through an example.

M1 contains hashslots from 0 to 8191.

M2 contains hashslots from 8192 to 16383.

So to map foo, we take a deterministic hash of the key (foo) and mod it by the number of hash slots(16K), leading to a mapping of M2. Now let's say we add a new instance, M3. The new mappings would be

M1 contains hashslots from 0 to 5460.

M2 contains hashslots from 5461 to 10922.

M3 contains hashslots from 10923 to 16383.

All the keys that mapped the hashslots in M1 that are now mapped to M2 would need to move. But the hashing for the individual keys to hashslots wouldn't need to move because they have already been divided up across hashslots. So this one level of misdirection solves the resharding issue with algorithmic sharding.

Gossiping

Redis Cluster uses gossiping to determine the entire cluster's health. In the illustration above, we have 3 M nodes and 3 S nodes. All these nodes constantly communicate to know which shards are available and ready to serve requests. If enough shards agree that M1 isn't responsive, they can decide to promote M1's secondary S1 into a primary to keep the cluster healthy. The number of nodes needed to trigger this is configurable, and it is essential to get this right. If you do it improperly, you can end up in situations where the cluster is split if it cannot break the tie when both sides of a partition are equal. This phenomenon is called split brain. As a general rule, it is essential to have an odd number of primary nodes and two replicas each for the most robust setup.

Redis Persistence Models

If we are going to use Redis to store any kind of data for safe keeping, it's important to understand how Redis is doing it. There are many usecases where if you were to lose the data Redis is storing is not the end of the world. Using it as a cache or in situations where its powering real-time analytics where if data loss occurs its no the end of the world.

In other scenarios, we want to have some guarantees around data persistence and recovery.

No persistence

No persistence: If you wish, you can disable persistence altogether. This is the fastest way to run Redis and has no durability guarantees.

Redis Database Files

RDB (Redis Database): The RDB persistence performs point-in-time snapshots of your dataset at specified intervals.

The main downside to this mechanism is that data between snapshots will be lost. In addition, this storage mechanism also relies on forking the main process, and in a larger dataset, this may lead to a momentary delay in serving requests. That being said, RDB files are much faster being loaded in memory than AOF.

RDB advantages:

-

RDB is a very compact single-file point-in-time representation of your Redis data. RDB files are perfect for backups. For instance you may want to archive your RDB files every hour for the latest 24 hours, and to save an RDB snapshot every day for 30 days. This allows you to easily restore different versions of the data set in case of disasters.

-

RDB is very good for disaster recovery, being a single compact file that can be transferred to far data centers, or onto Amazon S3 (possibly encrypted).

-

RDB maximizes Redis performances since the only work the Redis parent process needs to do in order to persist is forking a child that will do all the rest. The parent process will never perform disk I/O or alike.

-

RDB allows faster restarts with big datasets compared to AOF.

-

On replicas, RDB supports partial resynchronizations after restarts and failovers.

RDB disadvantages:

-

RDB is NOT good if you need to minimize the chance of data loss in case Redis stops working (for example after a power outage). You can configure different save points where an RDB is produced (for instance after at least five minutes and 100 writes against the data set, you can have multiple save points). However you'll usually create an RDB snapshot every five minutes or more, so in case of Redis stopping working without a correct shutdown for any reason you should be prepared to lose the latest minutes of data.

-

RDB needs to fork() often in order to persist on disk using a child process. fork() can be time consuming if the dataset is big, and may result in Redis stopping serving clients for some milliseconds or even for one second if the dataset is very big and the CPU performance is not great. AOF also needs to fork() but less frequently and you can tune how often you want to rewrite your logs without any trade-off on durability.

Append Only File

AOF (Append Only File): The AOF persistence logs every write operation the server receives that will be played again at server startup, reconstructing the original dataset.

AOF advantages:

-

Using AOF Redis is much more durable: you can have different fsync policies: no fsync at all, fsync every second, fsync at every query. With the default policy of fsync every second, write performance is still great. fsync is performed using a background thread and the main thread will try hard to perform writes when no fsync is in progress, so you can only lose one second worth of writes.

-

The AOF log is an append-only log, so there are no seeks, nor corruption problems if there is a power outage. Even if the log ends with a half-written command for some reason (disk full or other reasons) the redis-check-aof tool is able to fix it easily.

-

Redis is able to automatically rewrite the AOF in background when it gets too big. The rewrite is completely safe as while Redis continues appending to the old file, a completely new one is produced with the minimal set of operations needed to create the current data set, and once this second file is ready Redis switches the two and starts appending to the new one.

-

AOF contains a log of all the operations one after the other in an easy to understand and parse format. You can even easily export an AOF file. For instance even if you've accidentally flushed everything using the FLUSHALL command, as long as no rewrite of the log was performed in the meantime, you can still save your data set just by stopping the server, removing the latest command, and restarting Redis again.

AOF disadvantages:

-

AOF files are usually bigger than the equivalent RDB files for the same dataset.

-

AOF can be slower than RDB depending on the exact fsync policy. In general with fsync set to every second performance is still very high, and with fsync disabled it should be exactly as fast as RDB even under high load. Still RDB is able to provide more guarantees about the maximum latency even in the case of a huge write load.

How durable is the append only file? You can configure how many times Redis will fsync data on disk. There are three options:

-

appendfsync always: fsync every time new commands are appended to the AOF. Very very slow, very safe. Note that the commands are appended to the AOF after a batch of commands from multiple clients or a pipeline are executed, so it means a single write and a single fsync (before sending the replies).

-

appendfsync everysec: fsync every second. Fast enough (since version 2.4 likely to be as fast as snapshotting), and you may lose 1 second of data if there is a disaster.

-

appendfsync no: Never fsync, just put your data in the hands of the Operating System. The faster and less safe method. Normally Linux will flush data every 30 seconds with this configuration, but it's up to the kernel's exact tuning.

The suggested (and default) policy is to fsync every second. It is both fast and relatively safe. The always policy is very slow in practice, but it supports group commit, so if there are multiple parallel writes Redis will try to perform a single fsync operation.

What should I do if my AOF gets truncated?

It is possible the server crashed while writing the AOF file, or the volume where the AOF file is stored was full at the time of writing. When this happens the AOF still contains consistent data representing a given point-in-time version of the dataset (that may be old up to one second with the default AOF fsync policy), but the last command in the AOF could be truncated. The latest major versions of Redis will be able to load the AOF anyway, just discarding the last non well formed command in the file. In this case the server will emit a log like the following:

* Reading RDB preamble from AOF file...

* Reading the remaining AOF tail...

# !!! Warning: short read while loading the AOF file !!!

# !!! Truncating the AOF at offset 439 !!!

# AOF loaded anyway because aof-load-truncated is enabled

You can change the default configuration to force Redis to stop in such cases if you want, but the default configuration is to continue regardless of the fact the last command in the file is not well-formed, in order to guarantee availability after a restart.

What should I do if my AOF gets corrupted?

If the AOF file is not just truncated, but corrupted with invalid byte sequences in the middle, things are more complex. Redis will complain at startup and will abort:

* Reading the remaining AOF tail...

# Bad file format reading the append only file: make a backup of your AOF file, then use ./redis-check-aof --fix <filename>

The best thing to do is to run the redis-check-aof utility, initially without the --fix option, then understand the problem, jump to the given offset in the file, and see if it is possible to manually repair the file: The AOF uses the same format of the Redis protocol and is quite simple to fix manually. Otherwise it is possible to let the utility fix the file for us, but in that case all the AOF portion from the invalid part to the end of the file may be discarded, leading to a massive amount of data loss if the corruption happened to be in the initial part of the file.

Why not both?

RDB + AOF: It is possible to combine AOF and RDB in the same Redis instance. If durability in exchange for some speed is a tradeoff, you are willing to make it. I think this is an acceptable way to set up Redis. In the case of a restart, remember that if both are enabled, Redis will use AOF to reconstruct the data since it's the most complete.

In general, use the following list for durability VS latency/performance tradeoffs, ordered from stronger safety to better latency.

- AOF + fsync always: this is very slow, you should use it only if you know what you are doing.

- AOF + fsync every second: this is a good compromise.

- AOF + fsync every second + no-appendfsync-on-rewrite option set to yes: this is as the above, but avoids to fsync during rewrites to lower the disk pressure.

- AOF + fsync never. Fsyncing is up to the kernel in this setup, even less disk pressure and risk of latency spikes.

- RDB. Here you have a vast spectrum of tradeoffs depending on the save triggers you configure.

Factors impacting Redis performance

There are multiple factors having direct consequences on Redis performance. We mention them here, since they can alter the result of any benchmarks. Please note however, that a typical Redis instance running on a low end, untuned box usually provides good enough performance for most applications.

-

Network bandwidth and latency usually have a direct impact on the performance. It is a good practice to use the ping program to quickly check the latency between the client and server hosts is normal before launching the benchmark. Regarding the bandwidth, it is generally useful to estimate the throughput in Gbit/s and compare it to the theoretical bandwidth of the network. For instance a benchmark setting 4 KB strings in Redis at 100000 q/s, would actually consume 3.2 Gbit/s of bandwidth and probably fit within a 10 Gbit/s link, but not a 1 Gbit/s one. In many real world scenarios, Redis throughput is limited by the network well before being limited by the CPU. To consolidate several high-throughput Redis instances on a single server, it worth considering putting a 10 Gbit/s NIC or multiple 1 Gbit/s NICs with TCP/IP bonding.

-

CPU is another very important factor. Being single-threaded, Redis favors fast CPUs with large caches and not many cores. At this game, Intel CPUs are currently the winners. It is not uncommon to get only half the performance on an AMD Opteron CPU compared to similar Nehalem EP/Westmere EP/Sandy Bridge Intel CPUs with Redis. When client and server run on the same box, the CPU is the limiting factor with redis-benchmark.

-

Speed of RAM and memory bandwidth seem less critical for global performance especially for small objects. For large objects (>10 KB), it may become noticeable though. Usually, it is not really cost-effective to buy expensive fast memory modules to optimize Redis.

-

Redis runs slower on a VM compared to running without virtualization using the same hardware. If you have the chance to run Redis on a physical machine this is preferred. However this does not mean that Redis is slow in virtualized environments, the delivered performances are still very good and most of the serious performance issues you may incur in virtualized environments are due to over-provisioning, non-local disks with high latency, or old hypervisor software that have slow fork syscall implementation.

-

When the server and client benchmark programs run on the same box, both the TCP/IP loopback and unix domain sockets can be used. Depending on the platform, unix domain sockets can achieve around 50% more throughput than the TCP/IP loopback (on Linux for instance). The default behavior of redis-benchmark is to use the TCP/IP loopback.

-

The performance benefit of unix domain sockets compared to TCP/IP loopback tends to decrease when pipelining is heavily used (i.e. long pipelines).

-

When an ethernet network is used to access Redis, aggregating commands using pipelining is especially efficient when the size of the data is kept under the ethernet packet size (about 1500 bytes). Actually, processing 10 bytes, 100 bytes, or 1000 bytes queries almost result in the same throughput.

Latency Diagnosis

In this context latency is the maximum delay between the time a client issues a command and the time the reply to the command is received by the client. Usually Redis processing time is extremely low, in the sub microsecond range, but there are certain conditions leading to higher latency figures.

The following documentation is very important in order to run Redis in a low latency fashion. However I understand that we are busy people, so let's start with a quick checklist.

- Make sure you are not running slow commands that are blocking the server. Use the Redis Slow Log feature to check this.

- For EC2 users, make sure you use HVM based modern EC2 instances, like m3.medium. Otherwise fork() is too slow.

- Transparent huge pages must be disabled from your kernel. Use echo never > /sys/kernel/mm/transparent_hugepage/enabled to disable them, and restart your Redis process.

- If you are using a virtual machine, it is possible that you have an intrinsic latency that has nothing to do with Redis. Check the minimum latency you can expect from your runtime environment using

./redis-cli --intrinsic-latency 100. Note: you need to run this command in the server not in the client. Enable and use the Latency monitor feature of Redis in order to get a human readable description of the latency events and causes in your Redis instance.

Latency Baseline

There is a kind of latency that is inherently part of the environment where you run Redis, that is the latency provided by your operating system kernel and, if you are using virtualization, by the hypervisor you are using.

While this latency can't be removed it is important to study it because it is the baseline, or in other words, you won't be able to achieve a Redis latency that is better than the latency that every process running in your environment will experience because of the kernel or hypervisor implementation or setup.

We call this kind of latency intrinsic latency, and redis-cli starting from Redis version 2.8.7 is able to measure it. This is an example run under Linux 3.11.0 running on an entry level server.

Note: the argument 100 is the number of seconds the test will be executed. The more time we run the test, the more likely we'll be able to spot latency spikes. 100 seconds is usually appropriate, however you may want to perform a few runs at different times. Please note that the test is CPU intensive and will likely saturate a single core in your system.

$ ./redis-cli --intrinsic-latency 100

Max latency so far: 1 microseconds.

Max latency so far: 16 microseconds.

Max latency so far: 50 microseconds.

Max latency so far: 53 microseconds.

Max latency so far: 83 microseconds.

Max latency so far: 115 microseconds.

Note: redis-cli in this special case needs to run in the server where you run or plan to run Redis, not in the client. In this special mode redis-cli does not connect to a Redis server at all: it will just try to measure the largest time the kernel does not provide CPU time to run to the redis-cli process itself.

In the above example, the intrinsic latency of the system is just 0.115 milliseconds (or 115 microseconds), which is a good news, however keep in mind that the intrinsic latency may change over time depending on the load of the system.

Virtualized environments will not show so good numbers, especially with high load or if there are noisy neighbors. The following is a run on a Linode 4096 instance running Redis and Apache:

$ ./redis-cli --intrinsic-latency 100

Max latency so far: 573 microseconds.

Max latency so far: 695 microseconds.

Max latency so far: 919 microseconds.

Max latency so far: 1606 microseconds.

Max latency so far: 3191 microseconds.

Max latency so far: 9243 microseconds.

Max latency so far: 9671 microseconds.

Here we have an intrinsic latency of 9.7 milliseconds: this means that we can't ask better than that to Redis. However other runs at different times in different virtualization environments with higher load or with noisy neighbors can easily show even worse values. We were able to measure up to 40 milliseconds in systems otherwise apparently running normally.

Latency generated by slow commands

A consequence of being single thread is that when a request is slow to serve all the other clients will wait for this request to be served. When executing normal commands, like GET or SET or LPUSH this is not a problem at all since these commands are executed in constant (and very small) time. However there are commands operating on many elements, like SORT, LREM, SUNION and others. For instance taking the intersection of two big sets can take a considerable amount of time.

If you have latency concerns you should either not use slow commands against values composed of many elements, or you should run a replica using Redis replication where you run all your slow queries.

It is possible to monitor slow commands using the Redis Slow Log feature.

Additionally, you can use your favorite per-process monitoring program (top, htop, prstat, etc ...) to quickly check the CPU consumption of the main Redis process. If it is high while the traffic is not, it is usually a sign that slow commands are used.

IMPORTANT NOTE: a VERY common source of latency generated by the execution of slow commands is the use of the KEYS command in production environments. KEYS, as documented in the Redis documentation, should only be used for debugging purposes. Since Redis 2.8 a new commands were introduced in order to iterate the key space and other large collections incrementally, please check the SCAN, SSCAN, HSCAN and ZSCAN commands for more information.

Latency generated by fork

In order to generate the RDB file in background, or to rewrite the Append Only File if AOF persistence is enabled, Redis has to fork background processes. The fork operation (running in the main thread) can induce latency by itself.

Forking is an expensive operation on most Unix-like systems, since it involves copying a good number of objects linked to the process. This is especially true for the page table associated to the virtual memory mechanism.

For instance on a Linux/AMD64 system, the memory is divided in 4 kB pages. To convert virtual addresses to physical addresses, each process stores a page table (actually represented as a tree) containing at least a pointer per page of the address space of the process. So a large 24 GB Redis instance requires a page table of 24 GB / 4 kB * 8 = 48 MB.

When a background save is performed, this instance will have to be forked, which will involve allocating and copying 48 MB of memory. It takes time and CPU, especially on virtual machines where allocation and initialization of a large memory chunk can be expensive.

Latency induced by swapping (operating system paging)

Linux (and many other modern operating systems) is able to relocate memory pages from the memory to the disk, and vice versa, in order to use the system memory efficiently.

If a Redis page is moved by the kernel from the memory to the swap file, when the data stored in this memory page is used by Redis (for example accessing a key stored into this memory page) the kernel will stop the Redis process in order to move the page back into the main memory. This is a slow operation involving random I/Os (compared to accessing a page that is already in memory) and will result into anomalous latency experienced by Redis clients.

The kernel relocates Redis memory pages on disk mainly because of three reasons:

-

The system is under memory pressure since the running processes are demanding more physical memory than the amount that is available. The simplest instance of this problem is simply Redis using more memory than is available.

-

The Redis instance data set, or part of the data set, is mostly completely idle (never accessed by clients), so the kernel could swap idle memory pages on disk. This problem is very rare since even a moderately slow instance will touch all the memory pages often, forcing the kernel to retain all the pages in memory.

-

Some processes are generating massive read or write I/Os on the system. Because files are generally cached, it tends to put pressure on the kernel to increase the filesystem cache, and therefore generate swapping activity. Please note it includes Redis RDB and/or AOF background threads which can produce large files.

Fortunately Linux offers good tools to investigate the problem, so the simplest thing to do is when latency due to swapping is suspected is just to check if this is the case.

The first thing to do is to checking the amount of Redis memory that is swapped on disk. In order to do so you need to obtain the Redis instance pid:

$ redis-cli info | grep process_id

process_id:5454

Now enter the /proc file system directory for this process:

$ cd /proc/5454

Here you'll find a file called smaps that describes the memory layout of the Redis process (assuming you are using Linux 2.6.16 or newer). This file contains very detailed information about our process memory maps, and one field called Swap is exactly what we are looking for. However there is not just a single swap field since the smaps file contains the different memory maps of our Redis process (The memory layout of a process is more complex than a simple linear array of pages).

Since we are interested in all the memory swapped by our process the first thing to do is to grep for the Swap field across all the file:

$ cat smaps | grep 'Swap:'

Swap: 0 kB

Swap: 0 kB

Swap: 0 kB

Swap: 0 kB

Swap: 0 kB

Swap: 12 kB

Swap: 156 kB

Swap: 8 kB

Swap: 0 kB

Swap: 0 kB

Swap: 0 kB

Swap: 0 kB

Swap: 0 kB

Swap: 0 kB

Swap: 0 kB

Swap: 0 kB

Swap: 0 kB

Swap: 4 kB

If everything is 0 kB, or if there are sporadic 4k entries, everything is perfectly normal. Actually in our example instance (the one of a real web site running Redis and serving hundreds of users every second) there are a few entries that show more swapped pages. To investigate if this is a serious problem or not we change our command in order to also print the size of the memory map:

If instead a non trivial amount of the process memory is swapped on disk your latency problems are likely related to swapping. If this is the case with your Redis instance you can further verify it using the vmstat command:

$ vmstat 1

procs -----------memory---------- ---swap-- -----io---- -system-- ----cpu----

r b swpd free buff cache si so bi bo in cs us sy id wa

0 0 3980 697932 147180 1406456 0 0 2 2 2 0 4 4 91 0

0 0 3980 697428 147180 1406580 0 0 0 0 19088 16104 9 6 84 0

0 0 3980 697296 147180 1406616 0 0 0 28 18936 16193 7 6 87 0

0 0 3980 697048 147180 1406640 0 0 0 0 18613 15987 6 6 88 0

2 0 3980 696924 147180 1406656 0 0 0 0 18744 16299 6 5 88 0

0 0 3980 697048 147180 1406688 0 0 0 4 18520 15974 6 6 88 0

^C

The interesting part of the output for our needs are the two columns si and so, that counts the amount of memory swapped from/to the swap file. If you see non zero counts in those two columns then there is swapping activity in your system.

Finally, the iostat command can be used to check the global I/O activity of the system.

$ iostat -xk 1

avg-cpu: %user %nice %system %iowait %steal %idle

13.55 0.04 2.92 0.53 0.00 82.95

Device: rrqm/s wrqm/s r/s w/s rkB/s wkB/s avgrq-sz avgqu-sz await svctm %util

sda 0.77 0.00 0.01 0.00 0.40 0.00 73.65 0.00 3.62 2.58 0.00

sdb 1.27 4.75 0.82 3.54 38.00 32.32 32.19 0.11 24.80 4.24 1.85

If your latency problem is due to Redis memory being swapped on disk you need to lower the memory pressure in your system, either adding more RAM if Redis is using more memory than the available, or avoiding running other memory hungry processes in the same system.

Latency due to AOF and disk I/O

Another source of latency is due to the Append Only File support on Redis. The AOF basically uses two system calls to accomplish its work. One is write(2) that is used in order to write data to the append only file, and the other one is fdatasync(2) that is used in order to flush the kernel file buffer on disk in order to ensure the durability level specified by the user.

Both the write(2) and fdatasync(2) calls can be source of latency. For instance write(2) can block both when there is a system wide sync in progress, or when the output buffers are full and the kernel requires to flush on disk in order to accept new writes.

The fdatasync(2) call is a worse source of latency as with many combinations of kernels and file systems used it can take from a few milliseconds to a few seconds to complete, especially in the case of some other process doing I/O. For this reason when possible Redis does the fdatasync(2) call in a different thread since Redis 2.4.

The AOF can be configured to perform a fsync on disk in three different ways using the appendfsync configuration option (this setting can be modified at runtime using the CONFIG SET command).

-

When appendfsync is set to the value of no Redis performs no fsync. In this configuration the only source of latency can be write(2). When this happens usually there is no solution since simply the disk can't cope with the speed at which Redis is receiving data, however this is uncommon if the disk is not seriously slowed down by other processes doing I/O.

-

When appendfsync is set to the value of everysec Redis performs a fsync every second. It uses a different thread, and if the fsync is still in progress Redis uses a buffer to delay the write(2) call up to two seconds (since write would block on Linux if a fsync is in progress against the same file). However if the fsync is taking too long Redis will eventually perform the write(2) call even if the fsync is still in progress, and this can be a source of latency.

-

When appendfsync is set to the value of always a fsync is performed at every write operation before replying back to the client with an OK code (actually Redis will try to cluster many commands executed at the same time into a single fsync). In this mode performances are very low in general and it is strongly recommended to use a fast disk and a file system implementation that can perform the fsync in short time.

Most Redis users will use either the no or everysec setting for the appendfsync configuration directive. The suggestion for minimum latency is to avoid other processes doing I/O in the same system. Using an SSD disk can help as well, but usually even non SSD disks perform well with the append only file if the disk is spare as Redis writes to the append only file without performing any seek.

If you want to investigate your latency issues related to the append only file you can use the strace command under Linux:

sudo strace -p $(pidof redis-server) -T -e trace=fdatasync

The above command will show all the fdatasync(2) system calls performed by Redis in the main thread. With the above command you'll not see the fdatasync system calls performed by the background thread when the appendfsync config option is set to everysec. In order to do so just add the -f switch to strace.

If you wish you can also see both fdatasync and write system calls with the following command:

sudo strace -p $(pidof redis-server) -T -e trace=fdatasync,write

However since write(2) is also used in order to write data to the client sockets this will likely show too many things unrelated to disk I/O. Apparently there is no way to tell strace to just show slow system calls so I use the following command:

sudo strace -f -p $(pidof redis-server) -T -e trace=fdatasync,write 2>&1 | grep -v '0.0' | grep -v unfinished

Debugging Redis

When Redis crashes, it produces a detailed report of what happened. However, sometimes looking at the crash report is not enough, nor is it possible for the Redis core team to reproduce the issue independently. In this scenario, we need help from the user who can reproduce the issue.

This guide shows how to use GDB to provide the information the Redis developers will need to track the bug more easily.

GDB is the Gnu Debugger: a program that is able to inspect the internal state of another program. Usually tracking and fixing a bug is an exercise in gathering more information about the state of the program at the moment the bug happens, so GDB is an extremely useful tool.

GDB can be used in two ways:

- It can attach to a running program and inspect the state of it at runtime.

- It can inspect the state of a program that already terminated using what is called a core file, that is, the image of the memory at the time the program was running.

- From the point of view of investigating Redis bugs we need to use both of these GDB modes. The user able to reproduce the bug attaches GDB to their running Redis instance, and when the crash happens, they create the core file that in turn the developer will use to inspect the Redis internals at the time of the crash.

This way the developer can perform all the inspections in his or her computer without the help of the user, and the user is free to restart Redis in their production environment.

Attaching GDB to a running process

If you have an already running Redis server, you can attach GDB to it, so that if Redis crashes it will be possible to both inspect the internals and generate a core dump file.

After you attach GDB to the Redis process it will continue running as usual without any loss of performance, so this is not a dangerous procedure.

In order to attach GDB the first thing you need is the process ID of the running Redis instance (the pid of the process). You can easily obtain it using redis-cli:

$ redis-cli info | grep process_id

process_id:58414

Login into your Redis server.

(Optional but recommended) Start screen or tmux or any other program that will make sure that your GDB session will not be closed if your ssh connection times out.

Attach GDB to the running Redis server by typing:

$ gdb <path-to-redis-executable> <pid>

GDB will start and will attach to the running server printing something like the following:

Reading symbols for shared libraries + done

0x00007fff8d4797e6 in epoll_wait ()

(gdb)

At this point GDB is attached but your Redis instance is blocked by GDB. In order to let the Redis instance continue the execution just type continue at the GDB prompt, and press enter.

(gdb) continue

Continuing.

Done! Now your Redis instance has GDB attached. Now you can wait for the next crash. :)

Now it's time to detach your screen/tmux session, if you are running GDB using it, by pressing Ctrl-a a key combination.

After the crash

Redis has a command to simulate a segmentation fault (in other words a bad crash) using the DEBUG SEGFAULT command (don't use it against a real production instance of course! So I'll use this command to crash my instance to show what happens in the GDB side:

(gdb) continue

Continuing.

Program received signal EXC_BAD_ACCESS, Could not access memory.

Reason: KERN_INVALID_ADDRESS at address: 0xffffffffffffffff

debugCommand (c=0x7ffc32005000) at debug.c:220

220 *((char*)-1) = 'x';

As you can see GDB detected that Redis crashed, and was even able to show me the file name and line number causing the crash. This is already much better than the Redis crash report back trace (containing just function names and binary offsets).

Forking

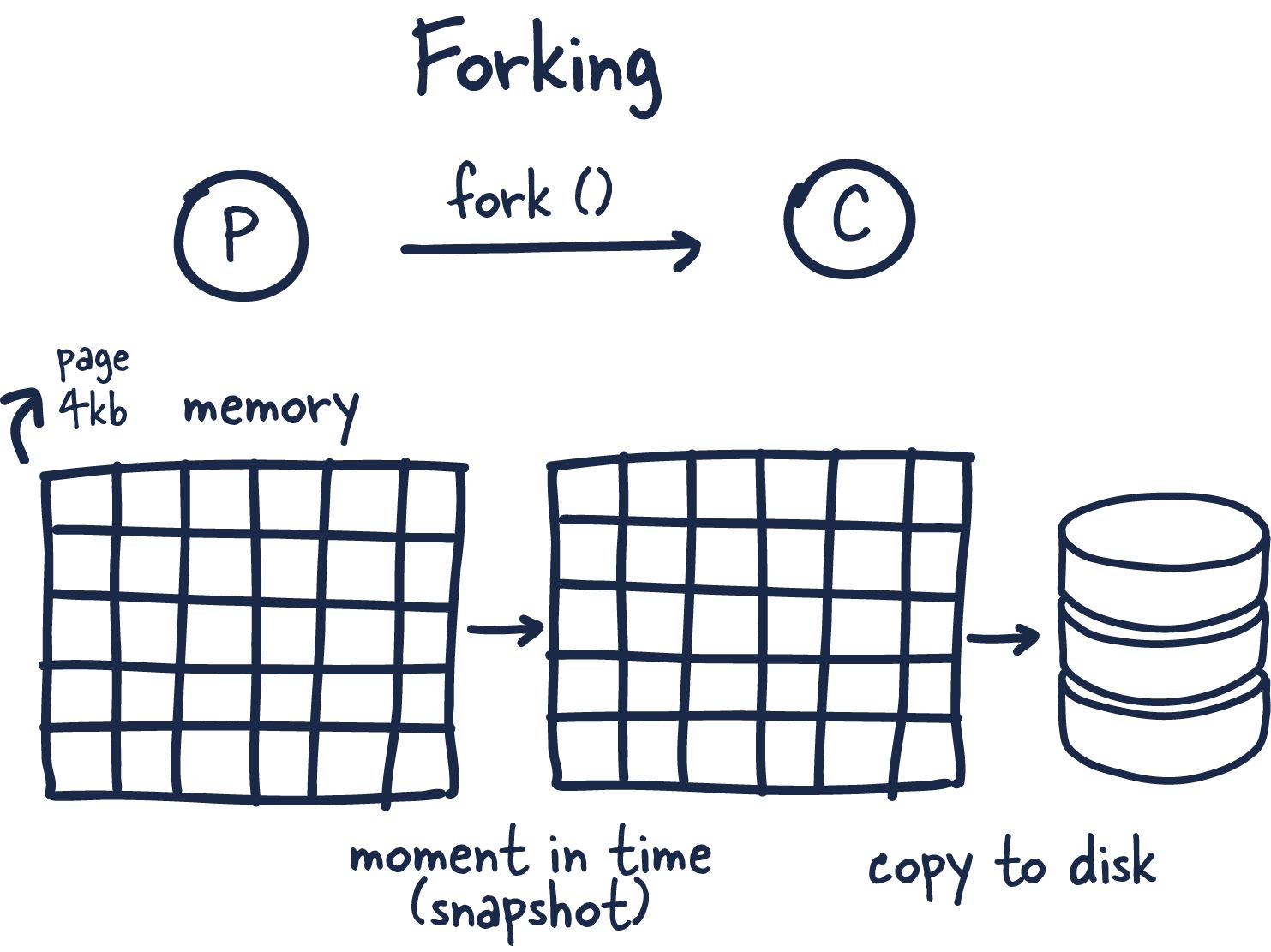

Now that we understand the types of persistence, let’s discuss how we actually go about doing it in a single threaded application like Redis.

This coolest part of Redis in my opinion is how it leverages forking and copy-on-write to facilitate data persistence performantly.

Forking is a way for operating systems to create new processes by creating copies of themselves. With this, you get a new process ID and a few other bits of information and handles, so the newly forked process (child) can talk to the original process parent.

Now here is where things get interesting. Redis is a process with tons of memory allocated to it, so how does it make a copy without running out of memory?

When you fork a process, the parent and child share memory, and in that child process Redis begins the snapshotting (Redis) process. This is made possible by a memory sharing technique called copy-on-write —which passses references to the memory at the time the fork was created. If no changes occur while the child process is persisting to disk, no new allocations are made.

In the case where there are changes, the kernel keeps track of references to each page, and if there are more than one to specific page the changes are written to new pages. The child process is fully unaware of the change and has consistent memory snapshot. Therefore only fraction of the memory is used and we are able to achieve a point in time snapshot of potentially gigabytes of memory extremely quickly and efficiently!

Setting Up a Redis Cluster

Now that we have a basic understanding of Redis clustering, let's set up a simple Redis cluster with three master nodes and three replica nodes. We'll assume you already have Redis installed on your system.

Configuring Redis Nodes First, create six directories for the Redis nodes, three for the master nodes and three for the replica nodes:

$ mkdir -p redis-cluster/{master,replica}/{1,2,3}

Next, create a Redis configuration file for each node. In each directory, create a redis.conf file with the following content

port 7000

cluster-enabled yes

cluster-config-file nodes.conf

cluster-node-timeout 5000

appendonly yes

Replace the port 7000 line with the appropriate port number for each node, e.g., 7001, 7002, etc.

Starting Redis Nodes

Now, start each Redis nodeusing the respective configuration file:

$ redis-server ./redis-cluster/master/1/redis.conf

$ redis-server ./redis-cluster/master/2/redis.conf

$ redis-server ./redis-cluster/master/3/redis.conf

$ redis-server ./redis-cluster/replica/1/redis.conf

$ redis-server ./redis-cluster/replica/2/redis.conf

$ redis-server ./redis-cluster/replica/3/redis.conf

Creating the Cluster Once all nodes are up and running, use the redis-cli command-line tool to create the cluster:

$ redis-cli --cluster create 127.0.0.1:7000 127.0.0.1:7001 127.0.0.1:7002 127.0.0.1:7003 127.0.0.1:7004 127.0.0.1:7005 --cluster-replicas 1

This command will create a cluster with the specified nodes, assigning one replica to each master node.

Working with Redis Cluster

Now that our Redis cluster is up and running, let's see how to interact with it using the redis-cli tool and a Python client library called redis-py-cluster.

To interact with the cluster using redis-cli, simply pass the --cluster option followed by the address of any node in the cluster:

$ redis-cli -c -h 127.0.0.1 -p 7000

Now you can use Redis commands as usual. The redis-cli tool will automatically handle cluster redirections:

> set foo "bar"

-> Redirected to slot [12182] located at 127.0.0.1:7002

OK

> get foo

-> Redirected to slot [12182] located at 127.0.0.1:7002

"bar"

Using redis-py-cluster To interact with the Redis cluster using Python, you'll need to install the redis-py-cluster library:

$ pip install redis-py-cluster

Then you can use the StrictRedisCluster class to connect to the cluster and execute Redis commands:

from rediscluster import StrictRedisCluster

startup_nodes = [{"host": "127.0.0.1", "port": "7000"}]

rc = StrictRedisCluster(startup_nodes=startup_nodes, decode_responses=True)

rc.set("foo", "bar")

print(rc.get("foo"))

This will output:

bar

Cluster Resharding and Failover

Redis Cluster provides built-in support for resharding and automatic failover. In this section, we'll discuss how to perform these operations.

Resharding Resharding is the process of redistributing hash slots among the nodes in the cluster. You can use the redis-cli tool to perform resharding.

First, let's list the nodes in the cluster:

$ redis-cli -c -h 127.0.0.1 -p 7000 cluster nodes

Note the node IDs of the nodes you want to move hash slots between. Then, use the redis-cli --cluster reshard command to initiate the resharding process:

$ redis-cli --cluster reshard 127.0.0.1:7000

Follow the prompts to specify the source and target nodes and the number of hash slots to move.

Redis Cluster automatically detects node failures and promotes a replica to a masternode if a master node becomes unavailable. This process is called failover. In addition to automatic failover, you can also perform manual failover using the redis-cli tool.

To perform a manual failover, first connect to the replica node that you want to promote to a master:

$ redis-cli -h 127.0.0.1 -p 7003

Then, use the CLUSTER FAILOVER command to initiate the failover process:

> CLUSTER FAILOVER

OK

Once the failover is complete, the replica node will be promoted to a master node, and the original master node will be demoted to a replica. The cluster will then update its configuration to reflect the new node roles.

Interview Questions

Is Redis just a cache?

Like a cache Redis offers:

- in memory key-value storage

But unlike a cache, Redis:

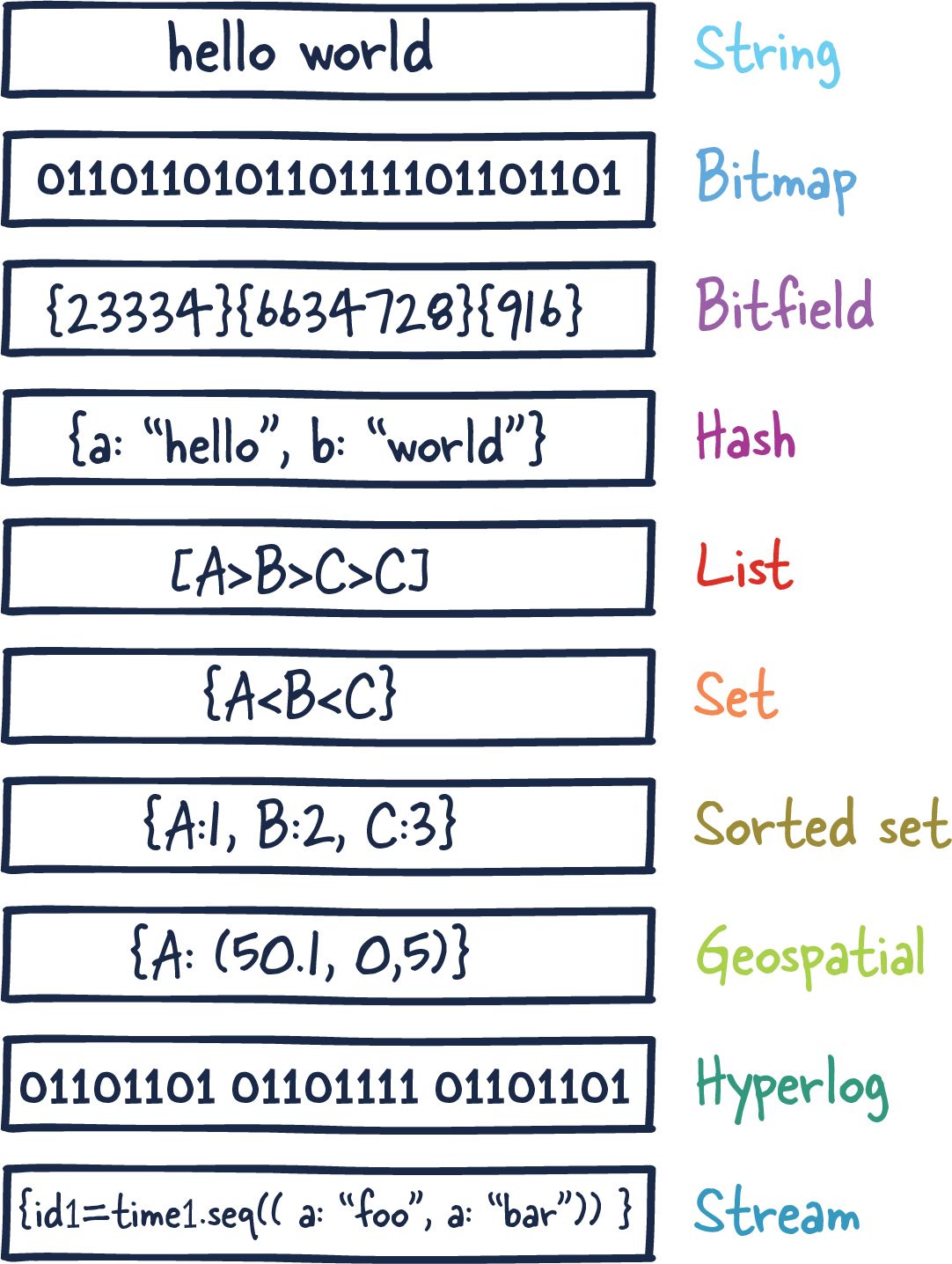

- Supports multiple datatypes (strings, hashes, lists, sets, sorted sets, bitmaps, and hyperloglogs)

- It provides an ability to store cache data into physical storage (if needed).

- Supports pub-sub model

- Redis cache provides replication for high availability (master/slave)

- Supports ultra-fast lua-scripts. Its execution time equals to C commands execution.

Does Redis persist data?

Redis supports so-called "snapshots". This means that it will do a complete copy of whats in memory at some points in time (e.g. every full hour). When you lose power between two snapshots, you will lose the data from the time between the last snapshot and the crash (doesn't have to be a power outage..). Redis trades data safety versus performance, like most NoSQL-DBs do.

Redis saves data in one of the following cases:

- automatically from time to time

- when you manually call

BGSAVEcommand - when redis is shutting down

But data in redis is not really persistent, because:

- crash of redis process means losing all changes since last save

BGSAVEoperation can only be performed if you have enough free RAM (the amount of extra RAM is equal to the size of redis DB)

What's the advantage of Redis vs using memory?

Redis is a remote data structure server. It is certainly slower than just storing the data in local memory (since it involves socket roundtrips to fetch/store the data). However, it also brings some interesting properties:

-

Redis can be accessed by all the processes of your applications, possibly running on several nodes (something local memory cannot achieve).

-

Redis memory storage is quite efficient, and done in a separate process. If the application runs on a platform whose memory is garbage collected (node.js, java, etc ...), it allows handling a much bigger memory cache/store. In practice, very large heaps do not perform well with garbage collected languages.

-

Redis can persist the data on disk if needed.

-

Redis is a bit more than a simple cache: it provides various data structures, various item eviction policies, blocking queues, pub/sub, atomicity, Lua scripting, etc ...

-

Redis can replicate its activity with a master/slave mechanism in order to implement high-availability.

Basically, if you need your application to scale on several nodes sharing the same data, then something like Redis (or any other remote key/value store) will be required.

When to use Redis Lists data type?

Redis lists are ordered collections of strings. They are optimized for inserting, reading, or removing values from the top or bottom (aka: left or right) of the list.

Redis provides many commands for leveraging lists, including commands to push/pop items, push/pop between lists, truncate lists, perform range queries, etc.

Lists make great durable, atomic, queues. These work great for job queues, logs, buffers, and many other use cases.

When to use Redis Sets?

Sets are unordered collections of unique values. They are optimized to let you quickly check if a value is in the set, quickly add/remove values, and to measure overlap with other sets.

These are great for things like access control lists, unique visitor trackers, and many other things. Most programming languages have something similar (usually called a Set). This is like that, only distributed.

Redis provides several commands to manage sets. Obvious ones like adding, removing, and checking the set are present. So are less obvious commands like popping/reading a random item and commands for performing unions and intersections with other sets.

When to use Redis over MongoDB?

It depends on kind of dev team you are and your application needs but some notes when to use Redis is probably a good idea:

- Caching

Caching using MongoDB simply doesn't make a lot of sense. It would be too slow.

- If you have enough time to think about your DB design.

You can't simply throw in your documents into Redis. You have to think of the way you in which you want to store and organize your data. One example are hashes in Redis. They are quite different from "traditional", nested objects, which means you'll have to rethink the way you store nested documents. One solution would be to store a reference inside the hash to another hash (something like key: [id of second hash]). Another idea would be to store it as JSON, which seems counter-intuitive to most people with a *SQL-background. Redis's non-traditional approach requires more effort to learn, but greater flexibility.

-

If you need really high performance.

Beating the performance Redis provides is nearly impossible. Imagine you database being as fast as your cache. That's what it feels like using Redis as a real database.

-

If you don't care that much about scaling.

Scaling Redis is not as hard as it used to be. For instance, you could use a kind of proxy server in order to distribute the data among multiple Redis instances. Master-slave replication is not that complicated, but distributing you keys among multiple Redis-instances needs to be done on the application site (e.g. using a hash-function, Modulo etc.). Scaling MongoDB by comparison is much simpler.

How are Redis pipelining and transaction different?

Pipelining is primarily a network optimization. It essentially means the client buffers up a bunch of commands and ships them to the server in one go. The commands are not guaranteed to be executed in a transaction. The benefit here is saving network round trip time for every command.

Redis is single threaded so an individual command is always atomic, but two given commands from different clients can execute in sequence, alternating between them for example.

Multi/exec, however, ensures no other clients are executing commands in between the commands in the multi/exec sequence.

Does Redis support transactions?

MULTI, EXEC, DISCARD and WATCH are the foundation of transactions in Redis. They allow the execution of a group of commands in a single step, with two important guarantees:

- All the commands in a transaction are serialized and executed sequentially. It can never happen that a request issued by another client is served in the middle of the execution of a Redis transaction. This guarantees that the commands are executed as a single isolated operation.

- Either all of the commands or none are processed, so a Redis transaction is also atomic.

How does Redis handle multiple threads (from different clients) updating the same data structure in Redis?

Redis is actually single-threaded, which is how every command is guaranteed to be atomic. While one command is executing, no other command will run.

A single-threaded program can definitely provide concurrency at the I/O level by using an I/O (de)multiplexing mechanism and an event loop (which is what Redis does). The fact that Redis operations are atomic is simply a consequence of the single-threaded event loop. The interesting point is atomicity is provided at no extra cost (it does not require synchronization between threads).

What is the difference between Redis replication and sharding?

- Sharding, also known as partitioning, is splitting the data up by key. Sharding is useful to increase performance, reducing the hit and memory load on any one resource.

- While replication, also known as mirroring, is to copy all data. Replication is useful for getting a high availability of reads. If you read from multiple replicas, you will also reduce the hit rate on all resources, but the memory requirement for all resources remains the same.

Any key-value store (of which Redis is only one example) supports sharding, though certain cross-key functions will no longer work. Redis supports replication out of the box.

When to use Redis Hashes data type?

Hashes are sort of like a key value store within a key value store. They map between string fields and string values. Field->value maps using a hash are slightly more space efficient than key->value maps using regular strings.

Hashes are useful as a namespace, or when you want to logically group many keys. With a hash you can grab all the members efficiently, expire all the members together, delete all the members together, etc. Great for any use case where you have several key/value pairs that need to grouped.

One example use of a hash is for storing user profiles between applications. A redis hash stored with the user ID as the key will allow you to store as many bits of data about a user as needed while keeping them stored under a single key. The advantage of using a hash instead of serializing the profile into a string is that you can have different applications read/write different fields within the user profile without having to worry about one app overriding changes made by others (which can happen if you serialize stale data).

Explain a use case for Sorted Set in Redis

Sorted Sets are also collections of unique values. These ones, as the name implies, are ordered. They are ordered by a score, then lexicographically.

This data type is optimized for quick lookups by score. Getting the highest, lowest, or any range of values in between is extremely fast.

If you add users to a sorted set along with their high score, you have yourself a perfect leader-board. As new high scores come in, just add them to the set again with their high score and it will re-order your leader-board. Also great for keeping track of the last time users visited and who is active in your application.

Storing values with the same score causes them to be ordered lexicographically (think alphabetically). This can be useful for things like auto-complete features.

Many of the sorted set commands are similar to commands for sets, sometimes with an additional score parameter. Also included are commands for managing scores and querying by score.

What is Pipelining in Redis and when to use one?

If you have many redis commands you want to execute you can use pipelining to send them to redis all-at-once instead of one-at-a-time.

Normally when you execute a command, each command is a separate request/response cycle. With pipelining, Redis can buffer several commands and execute them all at once, responding with all of the responses to all of your commands in a single reply.

This can allow you to achieve even greater throughput on bulk importing or other actions that involve lots of commands.

Mention what are the things you have to take care while using Redis?

- Select a consistent method to name and prefix your keys. Manage your namespace

- Create a “Registry” of key prefixes that maps each of your internal documents for that application which “own” them

- For every class you put through into your Redis infrastructure: design, implement and test the mechanisms for garbage collection or data migration to archival storage

- Design, implement and test a sharding library before you have invested much into your application deployment and make sure that you keep a registry of “shards “replicated on each server

- Separate all your K/V store and related operations into your own library/API or service

How can I exploit multiple CPU/cores for Redis?

First Redis is single threaded but it's not very frequent that CPU becomes your bottleneck with Redis, as usually Redis is either memory or network bound.

For instance, using pipelining Redis running on an average Linux system can deliver even 1 million requests per second, so if your application mainly uses O(N) or O(log n) commands, it is hardly going to use too much CPU.

However, to maximize CPU usage you can start multiple instances of Redis in the same box and treat them as different servers. At some point a single box may not be enough anyway, so if you want to use multiple CPUs you can start thinking of some way to shard earlier.

With Redis 4.0 Redis team started to make Redis more threaded. For now this is limited to deleting objects in the background, and to blocking commands implemented via Redis modules. For future releases, the plan is to make Redis more and more threaded.

What do the terms "CPU bound" and "I/O bound" mean in context of Redis?

-

A program is CPU bound if it would go faster if the CPU were faster, i.e. it spends the majority of its time simply using the CPU (doing calculations). A program that computes new digits of π will typically be CPU-bound, it's just crunching numbers.

-

A program is I/O bound if it would go faster if the I/O subsystem was faster. Which exact I/O system is meant can vary; I typically associate it with disk, but of course networking or communication in general is common too. A program that looks through a huge file for some data might become I/O bound, since the bottleneck is then the reading of the data from disk (actually, this example is perhaps kind of old-fashioned these days with hundreds of MB/s coming in from SSDs).

-

Memory bound means the rate at which a process progresses is limited by the amount memory available and the speed of that memory access. A task that processes large amounts of in memory data, for example multiplying large matrices, is likely to be Memory Bound.

-

Cache bound means the rate at which a process progress is limited by the amount and speed of the cache available. A task that simply processes more data than fits in the cache will be cache bound.

It's not very frequent that CPU becomes your bottleneck with Redis, as usually Redis is either memory or network bound.

Why Redis does not support roll backs?

Redis commands can fail during a transaction, but still Redis will execute the rest of the transaction instead of rolling back.

There are good opinions for this behavior:

- Redis commands can fail only if called with a wrong syntax (and the problem is not detectable during the command queueing), or against keys holding the wrong data type: this means that in practical terms a failing command is the result of a programming errors, and a kind of error that is very likely to be detected during development, and not in production.

- Redis is internally simplified and faster because it does not need the ability to roll back.

What is AOF persistence in Redis?

Redis AOF (Append Only Files) persistence logs every write operation received by the server, that will be played again at server startup, reconstructing the original dataset.

Redis must be explicitly configured for AOF persistence, if this is required, and this will result in a performance penalty as well as growing logs. It may suffice for relatively reliable persistence of a limited amount of data flow.

Is there a way to check if a key already exists in a redis list?

Your options are as follows:

- Using

LREMand replacing it if it was found. - Maintaining a separate

SETin conjunction with yourLIST - Looping through the

LISTuntil you find the item or reach the end.

What are the underlying data structures used for Redis?

Here is the underlying implementation of every Redis data type.

- Strings are implemented using a C dynamic string library so that we don't pay (asymptotically speaking) for allocations in append operations. This way we have

O(N)appends, for instance, instead of having quadratic behavior. - Lists are implemented with linked lists.

- Sets and Hashes are implemented with hash tables.

- Sorted sets are implemented with skip lists (a peculiar type of balanced trees).

- Zip List

- Int Sets

- Zip Maps (deprecated in favour of zip list since Redis 2.6)

It shall be also said that for every Redis operation you'll find the time complexity in the documentation so if you are not interested in Redis internals you should not care about how data types are implemented internally really.

How much faster is Redis than mongoDB?

- Rough results are 2x write, 3x read.

- The general answer is that Redis 10 - 30% faster when the data set fits within working memory of a single machine. Once that amount of data is exceeded, Redis fails.

- But your best bet is to benchmark them yourself, in precisely the manner you are intending to use them. As a corollary you'll probably figure out the best way to make use of each.

What happens if Redis runs out of memory?

Redis will either be killed by the Linux kernel OOM killer, crash with an error, or will start to slow down. With modern operating systems malloc() returning NULL is not common, usually the server will start swapping (if some swap space is configured), and Redis performance will start to degrade, so you'll probably notice there is something wrong.

Redis has built-in protections allowing the user to set a max limit to memory usage, using the maxmemory option in the configuration file to put a limit to the memory Redis can use. If this limit is reached Redis will start to reply with an error to write commands (but will continue to accept read-only commands), or you can configure it to evict keys when the max memory limit is reached in the case where you are using Redis for caching.

RDB and AOF, which one should I use?

-

The general indication is that you should use both persistence methods if you want a degree of data safety comparable to what PostgreSQL can provide you.

-

If you care a lot about your data, but still can live with a few minutes of data loss in case of disasters, you can simply use RDB alone.

Is Redis a durable datastore ("D" from ACID)?

Redis is not usually deployed as a "durable" datastore (in the sense of the "D" in ACID.), even with journaling. Most use cases intentionally sacrifice a little durability in return for speed.

However, the "append only file" storage mode can optionally be configured to operate in a durable manner, at the cost of performance. It will have to pay for an fsync() on every modification.

What is the best use of Redis?

Redis excels with its in-memory data storage capability, enabling quick read/write operations. This makes Redis an excellent choice for a caching layer, boosting the speed and performance of web applications. It's also adept at session management due to its fast access to user data. Additionally, Redis handles real-time analytics well thanks to its high throughput and data structures like sorted sets and bitmaps. Its Pub/Sub model is also an ideal fit as a message broker in microservices architectures.

How do you use Redis efficiently?

To use Redis efficiently, it's essential to select the most suitable data structures, which could be key-value pairs, sets, sorted sets, lists, or hashes, depending on your use case. Redis's in-memory nature demands regular memory management. You should make use of Redis Pipelining to group commands and reduce latency. Furthermore, consistent hashing can support efficient distribution and retrieval of data across various nodes. Always keep your Redis updated to benefit from the latest features and improvements, and remember to apply suitable indexing strategies for fast data access.

Why not use Redis for everything?

Although Redis is a powerful tool, it's not ideal for all scenarios. Its in-memory architecture may not be suitable for workloads that require persistent data storage. Redis lacks the support for complex queries and joins that traditional relational databases offer. It may not be the best option for heavy-duty transactional workloads due to its single-threaded nature. Additionally, the potential risk of data loss in the event of a system crash is a downside of Redis's in-memory design.

What is the best way to manage Redis connections?

Managing Redis connections efficiently often involves using connection pooling to minimize the overhead associated with opening and closing connections. Adjusting timeout settings to free up idle connections and save resources can also help. It's crucial to monitor your client connections to prevent hitting connection limits and to implement robust error-handling and retry mechanisms for dealing with connection failures. Lastly, using dedicated libraries or tools that provide high-level abstractions can be beneficial for connection management.

How can I protect my Redis server from unauthorized access?