SSL-TLS

What is SSL?

SSL, or Secure Sockets Layer, is an encryption-based Internet security protocol. It was first developed by Netscape in 1995 for the purpose of ensuring privacy, authentication, and data integrity in Internet communications. SSL is the predecessor to the modern TLS encryption used today.

A website that implements SSL/TLS has "HTTPS" in its URL instead of "HTTP."

How does SSL/TLS work?

- In order to provide a high degree of privacy, SSL encrypts data that is transmitted across the web. This means that anyone who tries to intercept this data will only see a garbled mix of characters that is nearly impossible to decrypt.

- SSL initiates an authentication process called a handshake between two communicating devices to ensure that both devices are really who they claim to be.

- SSL also digitally signs data in order to provide data integrity, verifying that the data is not tampered with before reaching its intended recipient.

There have been several iterations of SSL, each more secure than the last. In 1999 SSL was updated to become TLS.

Why is SSL/TLS important?

Originally, data on the Web was transmitted in plaintext that anyone could read if they intercepted the message. For example, if a consumer visited a shopping website, placed an order, and entered their credit card number on the website, that credit card number would travel across the Internet unconcealed.

SSL was created to correct this problem and protect user privacy. By encrypting any data that goes between a user and a web server, SSL ensures that anyone who intercepts the data can only see a scrambled mess of characters. The consumer's credit card number is now safe, only visible to the shopping website where they entered it.

SSL also stops certain kinds of cyber attacks: It authenticates web servers, which is important because attackers will often try to set up fake websites to trick users and steal data. It also prevents attackers from tampering with data in transit, like a tamper-proof seal on a medicine container.

Are SSL and TLS the same thing?

SSL is the direct predecessor of another protocol called TLS (Transport Layer Security). In 1999 the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) proposed an update to SSL. Since this update was being developed by the IETF and Netscape was no longer involved, the name was changed to TLS. The differences between the final version of SSL (3.0) and the first version of TLS are not drastic; the name change was applied to signify the change in ownership.

Since they are so closely related, the two terms are often used interchangeably and confused. Some people still use SSL to refer to TLS, others use the term "SSL/TLS encryption" because SSL still has so much name recognition.

What is an SSL certificate?

SSL certificates are what enable websites to use HTTPS, which is more secure than HTTP. An SSL certificate is a data file hosted in a website's origin server. SSL certificates make SSL/TLS encryption possible, and they contain the website's public key and the website's identity, along with related information.

Devices attempting to communicate with the origin server will reference this file to obtain the public key and verify the server's identity. The private key is kept secret and secure.

One of the most important pieces of information in an SSL certificate is the website's public key. The public key makes encryption and authentication possible. A user's device views the public key and uses it to establish secure encryption keys with the web server. Meanwhile the web server also has a private key that is kept secret; the private key decrypts data encrypted with the public key.

Certificate authorities (CA) are responsible for issuing SSL certificates.

How do SSL certificates work?

SSL certificates include the following information in a single data file:

- The domain name that the certificate was issued for

- Which person, organization, or device it was issued to

- Which certificate authority issued it

- The certificate authority's digital signature

- Associated subdomains

- Issue date of the certificate

- Expiration date of the certificate

- The public key (the private key is kept secret)

- The public and private keys used for SSL are essentially long strings of characters used for encrypting and signing data. Data encrypted with the public key can only be decrypted with the private key.

The certificate is hosted on a website's origin server, and is sent to any devices that request to load the website. Most browsers enable users to view the SSL certificate: in Chrome, this can be done by clicking on the padlock icon on the left side of the URL bar.

What are the types of SSL certificates?

There are several different types of SSL certificates. One certificate can apply to a single website or several websites, depending on the type:

-

Single-domain: A single-domain SSL certificate applies to only one domain (a "domain" is the name of a website, like www.cloudflare.com).

-

Wildcard: Like a single-domain certificate, a wildcard SSL certificate applies to only one domain. However, it also includes that domain's subdomains. For example, a wildcard certificate could cover www.cloudflare.com, blog.cloudflare.com, and developers.cloudflare.com, while a single-domain certificate could only cover the first.

-

Multi-domain: As the name indicates, multi-domain SSL certificates can apply to multiple unrelated domains.

SSL certificates also come with different validation levels. A validation level is like a background check, and the level changes depending on the thoroughness of the check.

-

Domain Validation: This is the least-stringent level of validation, and the cheapest. All a business has to do is prove they control the domain.

-

Organization Validation: This is a more hands-on process: The CA directly contacts the person or business requesting the certificate. These certificates are more trustworthy for users.

-

Extended Validation: This requires a full background check of an organization before the SSL certificate can be issued.

Why do websites need an SSL certificate?

A website needs an SSL certificate in order to keep user data secure, verify ownership of the website, prevent attackers from creating a fake version of the site, and gain user trust.

-

Encryption: SSL/TLS encryption is possible because of the public-private key pairing that SSL certificates facilitate. Clients (such as web browsers) get the public key necessary to open a TLS connection from a server's SSL certificate.

-

Authentication: SSL certificates verify that a client is talking to the correct server that actually owns the domain. This helps prevent domain spoofing and other kinds of attacks.

-

HTTPS: Most crucially for businesses, an SSL certificate is necessary for an HTTPS web address. HTTPS is the secure form of HTTP, and HTTPS websites are websites that have their traffic encrypted by SSL/TLS.

In addition to securing user data in transit, HTTPS makes sites more trustworthy from a user's perspective. Many users won't notice the difference between an http:// and an https:// web address, but most browsers tag HTTP sites as "not secure" in noticeable ways, attempting to provide incentive for switching to HTTPS and increasing security.

How does a website obtain an SSL certificate?

For an SSL certificate to be valid, domains need to obtain it from a certificate authority (CA). A CA is an outside organization, a trusted third party, that generates and gives out SSL certificates. The CA will also digitally sign the certificate with their own private key, allowing client devices to verify it. Most, but not all, CAs will charge a fee for issuing an SSL certificate.

Once the certificate is issued, it needs to be installed and activated on the website's origin server. Web hosting services can usually handle this for website operators. Once it's activated on the origin server, the website will be able to load over HTTPS and all traffic to and from the website will be encrypted and secure.

What is a self-signed SSL certificate?

Technically, anyone can create their own SSL certificate by generating a public-private key pairing and including all the information mentioned above. Such certificates are called self-signed certificates because the digital signature used, instead of being from a CA, would be the website's own private key.

But with self-signed certificates, there's no outside authority to verify that the origin server is who it claims to be. Browsers don't consider self-signed certificates trustworthy and may still mark sites with one as "not secure," despite the https:// URL. They may also terminate the connection altogether, blocking the website from loading.

TLS Handshake

TLS is an encryption and authentication protocol designed to secure Internet communications. A TLS handshake is the process that kicks off a communication session that uses TLS. During a TLS handshake, the two communicating sides exchange messages to acknowledge each other, verify each other, establish the cryptographic algorithms they will use, and agree on session keys. TLS handshakes are a foundational part of how HTTPS works.

TLS vs. SSL handshakes

SSL, or Secure Sockets Layer, was the original security protocol developed for HTTP. SSL was replaced by TLS, or Transport Layer Security, some time ago. SSL handshakes are now called TLS handshakes, although the "SSL" name is still in wide use.

When does a TLS handshake occur?

A TLS handshake takes place whenever a user navigates to a website over HTTPS and the browser first begins to query the website's origin server. A TLS handshake also happens whenever any other communications use HTTPS, including API calls and DNS over HTTPS queries.

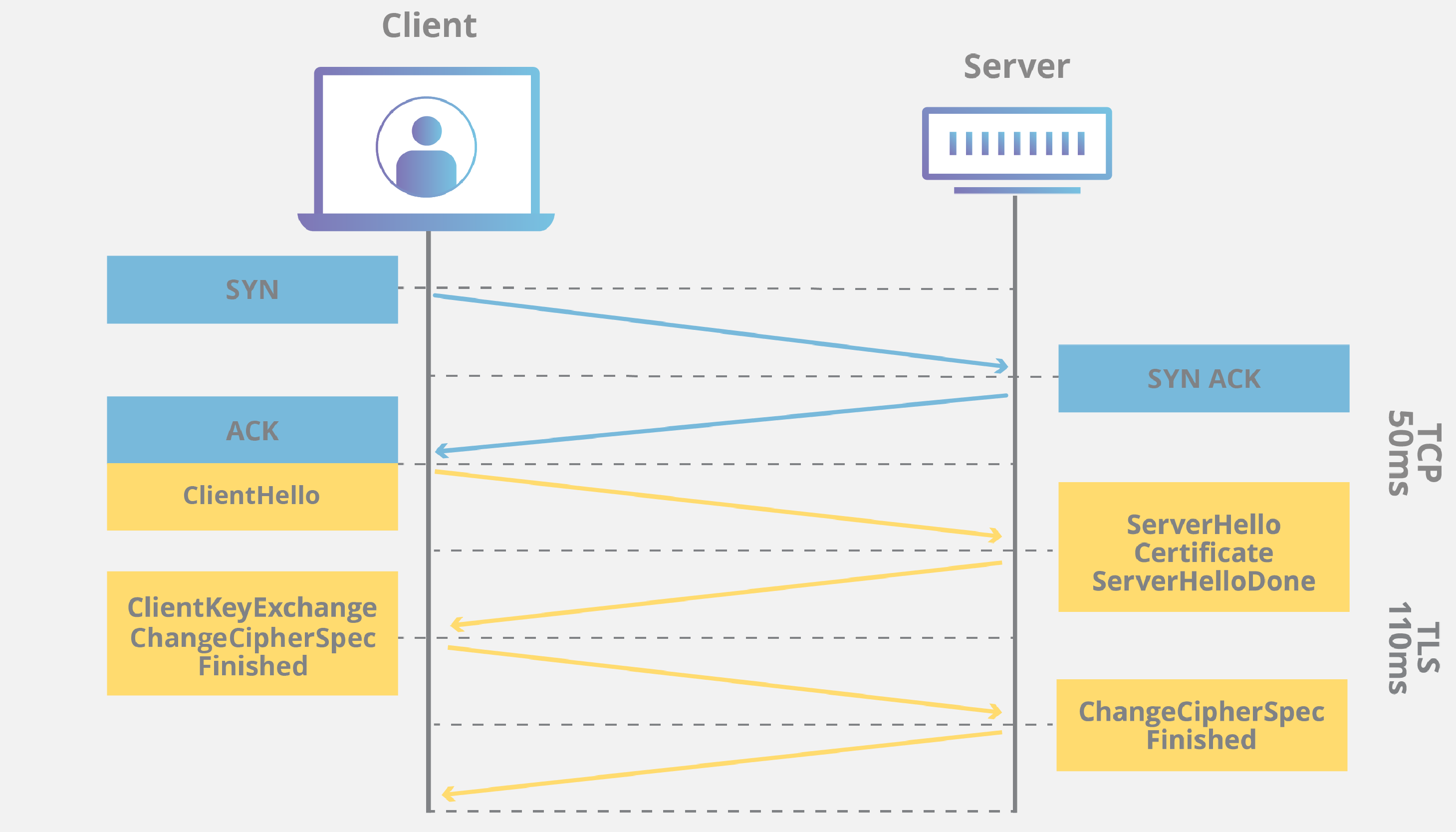

TLS handshakes occur after a TCP connection has been opened via a TCP handshake.

What happens during a TLS handshake?

During the course of a TLS handshake, the client and server together will do the following:

Specify which version of TLS (TLS 1.0, 1.2, 1.3, etc.) they will use Decide on which cipher suites (see below) they will use Authenticate the identity of the server via the server’s public key and the SSL certificate authority’s digital signature Generate session keys in order to use symmetric encryption after the handshake is complete:

Symmetric Key

Private Key/Public Key encryption algorithms are great, but they are not usually practical. It is asymmetric because you need the other key pair to decrypt. You can't use the same key to encrypt and decrypt. An algorithm using the same key to decrypt and encrypt is deemed to have a symmetric key. A symmetric algorithm is much faster in doing its job than an asymmetric algorithm. But a symmetric key is potentially highly insecure. If the enemy gets hold of the key then you have no more secret information. You must therefore transmit the key to the other party without the enemy getting its hands on it. As you know, nothing is secure on the Internet.

The solution is to encapsulate the symmetric key inside a message encrypted with an asymmetric algorithm. You have never transmitted your private key to anybody, then the message encrypted with the public key is secure (relatively secure, nothing is certain except death and taxes). The symmetric key is also chosen randomly, so that if the symmetric secret key is discovered then the next transaction will be totally different.

What are the steps of a TLS handshake?

TLS handshakes are a series of datagrams, or messages, exchanged by a client and a server. A TLS handshake involves multiple steps, as the client and server exchange the information necessary for completing the handshake and making further conversation possible.

The exact steps within a TLS handshake will vary depending upon the kind of key exchange algorithm used and the cipher suites supported by both sides. The RSA key exchange algorithm, while now considered not secure, was used in versions of TLS before 1.3. It goes roughly as follows:

- The 'client hello' message: The client initiates the handshake by sending a "hello" message to the server. The message will include which TLS version the client supports, the cipher suites supported, and a string of random bytes known as the "client random."

- The 'server hello' message: In reply to the client hello message, the server sends a message containing the server's SSL certificate, the server's chosen cipher suite, and the "server random," another random string of bytes that's generated by the server.

- Authentication: The client verifies the server's SSL certificate with the certificate authority that issued it. This confirms that the server is who it says it is, and that the client is interacting with the actual owner of the domain.

- The premaster secret: The client sends one more random string of bytes, the "premaster secret." The premaster secret is encrypted with the public key and can only be decrypted with the private key by the server. (The client gets the public key from the server's SSL certificate.)

- Private key used: The server decrypts the premaster secret.

- Session keys created: Both client and server generate session keys from the client random, the server random, and the premaster secret. They should arrive at the same results.

- Client is ready: The client sends a "finished" message that is encrypted with a session key.

- Server is ready: The server sends a "finished" message encrypted with a session key.

- Secure symmetric encryption achieved: The handshake is completed, and communication continues using the session keys.